Introduction

Cuba is beautiful, interesting, perplexing, but above all, I consider it the most controversial place on earth. Cuba means different things to different people around the world. Its geographic location is unequivocal, but the rest is up for interpretation. I’m Valentina, a Ph.D. candidate at McGill University and a proud Canadian-Venezuelan; I decided to organize my dual nationality alphabetically as today I can’t tell which country I belong the most. The reason why this matters is because I constantly find myself struggling to reconcile the contrasting notions that Canadians and Venezuelans have of Cuba. On the one hand, Canadians jump with joy when they hear I’m taking two weeks off my schedule (and teaching responsibilities—thanks to my professors for their understanding!) to visit Cuba. On the other hand, Venezuelans look at me in disbelief with their eyes full of fear and anger, asking me why am I doing such thing, couldn’t I go somewhere else? Anywhere…? The reasons behind each reaction are clear: for my fellows in the north, Cuba is a sunny paradise, and for my fellows in the south, it represents a notorious political ally of the Chavez-Maduro regime. They are both right. There is no Cuba without the sun and beach, but there is also no Cuba without treacherous political ideology. With this in mind, six months ago I applied to the SAH Study Program Fellowship and disclosed my unapologetic, politically charged research interest. I explained that a tour that closely looks at Cuban architecture throughout history could help us answer in what way political power plays a defining role in domestic architecture (my field of interest). There’s no better place than Cuba to contribute to answering this question. Full of joy and pride for the architectural education system, I get my bags ready to embark on this amazing trip.

Day 1. Saturday, Dec. 1st, 2018. Welcome to Miami, Bienvenidos a Miami!

There’s no better place to start our journey and to prepare us for Cuba like Miami. The “Latino Metropolis” houses around 1.8 million Cuban-Americans, which comprise 54% of its population. Cuban culture—from cafes and restaurants to the Museum of the Cuban Diaspora—has added to Miami’s vibrancy and azucar!

American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora

Illustration of Celia Cruz in the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora

I arrived at the hotel very excited. After all, this is no ordinary tour— all the participants share an immense passion for architecture. Gary, our tour operator, is waiting for us in the meeting room asking simply, “Architecture?” Gary is a tall, smiling fellow who spends half of his time in Cuba and will be our tour guide from beginning to end. The third person to arrive is Victoria Young, SAH’s First Vice President, an outstanding architectural historian, a strict timekeeper, a wonderful coordinator, and a delightful person to be around. Between cheerful greetings and joyful handshakes we distributed nametags and all the important documentation for our trip. Belmont (Monty) Freeman, a New York-based architect, writer, and Professor in Practice at Columbia University, is appointed to lead this tour; I’m sure that without his passion for Cuban architecture and personal and professional connections this trip wouldn’t have been as successful as it was. He brought not only a deep, grounded knowledge of architecture and the country, but most importantly, a sense of pride and belonging, which made us all honored to be seeing Cuba through his eyes. He delivered a very complete and sophisticated introduction to Cuba, which was the perfect appetizer for what was about to come. After we all introduced ourselves, we went to bed to prepare for an early morning flight that would take us to Havana.

Our first group gathering in the Miami Crowne Plaza

Day 2. December 2nd, 2018. Havana…. Here we go!

The hotel agreed to open the breakfast bar early that day especially for us. At 5:30 a.m. recognizing the faces from the night before, we started greeting each other and shared the table for a fueling breakfast of fresh fruits, cereals, pastries, and coffee. The buses that would take us to the airport were readily waiting at 6:20 a.m. Things went smoothly in the airport, we presented our documentation, checked in our bags, and patiently waited in long lines to make it through security. We boarded the plane, and 45 minutes later we were landing safely in Havana where our local tour guide, Lazaro, was waiting for us. “What’s your name?” we asked. “Lazaro,” he responded, followed by a mimic of someone coming back from the dead. We appreciated the biblical humor, which made it virtually impossible to forget his name. Lazaro was instrumental in making our trip safe, well-coordinated, and memorable. Trained at the University of Havana in international relations and close to completing his Ph.D. in Cuban history, he added precious knowledge that would help us understand Cuban history and society from an insider’s perspective. Lazaro’s perfect English and educated ways impressed us to the point that members of the group would line up to talk to him and ask many questions to which he would answer insightfully and honestly.

Freshly off the plane after retrieving our bags without inconveniences, Lazaro directed us to our bus—a big, long, blue and white Transtur guagua that we came to recognize as our comfortable second home in Cuba. The best thing about this bus that drove us all around the narrow streets of the cities and towns we visited wasn’t its efficient air-conditioning system or how clean it was, but the person driving it: Juanito. Juanito’s genteel ways, utterly professional driving, helping hand (always waiting for us at the bottom of the bus to avoid accidents), and persistent smile captivated us all and brought an extra good vibe into our trip.

Our bus and our reliable driver, Juanito.

Ready to begin the adventure, we each chose a seat on the bus, which, like schoolkids, we would always return to and seldom switched. As we drove to the city center for lunch, we made our first stop: Plaza de la Revolucion. This iconic square is a group of buildings and monuments devoted to the Cuban Revolution. Originally named Plaza Civica, the massive complex of monuments, buildings, and public space was planned by Jean Claude Forestier in the 1920s. On the northern part of the plaza, the Ministry of Interior, a 1958 grey concrete building serves as a canvas for the recognizable image of Che Guevara, by now impossible, at least for me, to disassociate from Fidel Castro. Che and Camilo Cienfuegos on its left act as the backdrop of political rallies, communist assemblies, and even a couple of high-profile Catholic masses like faithful servants to La Revolucion. On the other side of the street, overlooking the plaza, its events, and the city from an insurmountable height is the country’s national hero Jose Marti, father of the homeland. Marti’s monument is the largest built for a writer, it was designed by Raoul Otero de Galarraga and encased in Cuban marble.

Monty, Julie and David admire the Jose Marti Memorial.

A group of us posing for the picture in front of the iconic Ministry of Interior.

We continued our trip to Havana’s historic district where we walked around the San Francisco de Assis square and had lunch in the Restaurant Café Oriente. Our first lunch was a great opportunity to get to know each other while listening to a live piano performance and enjoying a nice meal (and a mojito or two, but who was keeping score?). After lunch, we drove to El Castillo del Morro, a solid Spanish fortress dating back to the 16th century originally built to guard Havana. Today, el Castillo has stood the test of time, and although it has been partly damaged and reconstructed in the 18th century, it remains a permanent reminder of the importance of Havana for the Spanish crown. Placed on top of a small hill, this massive stone structure observed from afar becomes an elegant linear composition, almost blending with the horizon line. The vibrant green of the grass and a contrasting blue sky add to the sense of the majesty of the Castillo and to our joy of being in Cuban territory.

Liliana tries to capture the beauty of the place while Steve and David talk.

David and Susanne take a selfie.

Castillo del Morro

Later, it was time to check in at our Hotel Parque Central, in the heart of the historic district of Havana. With an excessively decorated lobby, our hotel was pleasantly filled with light, vegetation, and with the sweet noises of music and cheerful people. After leaving our bags in the room and resting for a while, we headed out for lunch in a close-by paladar. We walked about two blocks south of our hotel into a well kept 18th-century building with high ceilings, big, massive wooden beams and tall, magnificent windows. Once inside the almost empty lobby of the building, we went up three flights of stairs into a covered rooftop, which overlooked the illuminated plaza. Eating—or, more accurately—offering food to tourists in the highest point of the building seems to be a national obsession. Maybe locals believe that the city is prettier from a safe distance. The menu of the Paladar La Terraza was a choice of grilled seafood or meat platter, which we enjoyed under a perfect starry night while the warm air breeze reminded us that we were in Havana!

Our hotel in Havana had a spacious lobby where we gathered every morning.

Lobby of the Terraza restaurant

Welcome dinner in Havana

More of our welcome dinner in La Terraza restaurant

Day 3. Walking through La Habana Vieja. December 3rd, 2018.

We met at the hotel lobby to start our walk through Old Havana. Our first stop was the Edificio Bacardi, an outstanding Art Deco building designed by Esteban Rodríguez-Castells and Rafael Fernández Ruenes and completed in 1930. Originally built as the headquarters for the Bacardi Rum company, it is arguably the best Art Deco building of Latin America and one of the finest examples in the world. Like the Bacardi Mansion we later visited in Santiago de Cuba, the government confiscated this building after the revolution and today both are used as office buildings. The only part of the building open to the public is the impeccably kept lobby, guarded by a watchman unperturbed by our presence. One thing I started noticing in Cuba’s tourism management is that they are cognizant of their architectural assets and take good care of them to keep the travelers (and their capital) flow to the island. The Bacardi Building entrance was impeccable, and its magnificent spotless golden lamps symbolize the government’s triumph over the unyielding Bacardi rum company. Right in front of this architectural gem is another rather dilapidated building, which evidences a different relationship with time and power. I couldn’t find any information on the name, date, or architect of this commercial hub, but I think it’s called Actualidades for the iron letters on its front, although I can’t be certain since five letters are missing. The Actualidades building hasn’t received any maintenance in years, but its tall arches, heavy iron lamps, and discreet moldings hint to a dignified past that is now long gone. There’s nothing really special about this building—there are thousands like it around Havana—but the contrast with the Bacardi building right in front of it inspired these lines. Back to the Bacardi building, we went inside the lavishly decorated lobby where every wall was covered with granite or marble, and the floors had intricate patterns of the same materials in exotic colors like red, orange, and yellow. Entering an Art Deco space (especially a lobby) is always a treat to the eyes and a reminder of a wealthier time filled with enthusiasm and jubilance, and this building brings that particular atmosphere to this area of Havana. While taking pictures of the marble, golden lamps, stain glass, and ironwork around the lobby, I developed a private exercise consisting of going inside and outside of the building, in and out, in and out…as a method of physically assimilating Cuba’s perplexing contrasts.

Our group in front of the facade of the Bacardi building

Facade of the Bacardi building

Edificio Actualidades

Interior of the Bacardi Building

The Bacardi Building inspired us in different ways. Our tour leaders had a hard time getting us out of the lobby.

Juanito and the bus awaited us a block away to see other parts of La Vieja Habana. We hopped in and spent a physically intense afternoon going around Old Havana, in and out of majestic colonial buildings. Initially, we gathered under the shadow of a leafy tree where we carefully listened to Monty explain the buildings surrounding the square. The Plaza de Armas dates to the 16th century and is the oldest square in Havana. The place we were occupying was considered at the beginning of the Spanish Colony as the administrative heart of this Captaincy General. Around this square proudly stood El Palacio de Los Capitanes Generales, El Templete, the Royal Post Office and El Castillo de la Real Fuerza. The group of buildings cohesively represent the power once bestowed on this city. We continued our walk towards the cathedral passing by a great number of beautiful and perfectly kept buildings.

Monty explaining the importance of El Templete while Paul carefully listens.

El Templete

Leafy trees and gallerias cast generous shadows for passersby.

We developed the habit of peeping through the heavy wooden doors where we would usually find hidden architectural elements and details like stairways, interior patios, doorways, and ironwork. Old Havana is a UNESCO World Heritage site, which differentiates this section of the city from the rest because every building in this area is fully restored and impeccably kept.

Interesting interiors in Old Havana

We made it to the cathedral, an exemplary piece of Cuban Baroque architecture. The slightly asymmetric two-tower building was built in 1748–1777 out of blocks of coral that gracefully reveal bits and pieces of fossilized sea life. The building underwent major renovations in 1946, which is probably why it’s very cohesive and homogenous in appearance.

Havana's cathedral

After visiting the cathedral, while walking through a narrow street, we encountered a small house close by which seemed to be out of place and out of scale. What interested me about it was a hand-painted sign above the door that read: Te Estoy Mirando, I’m looking at you. When I peeped inside its wide-open door, I spotted a Santero sitting inside who smiled at me and asked me to come in. I was really tempted but had to reject his offer to keep up with the group. While rushing to catch up with everyone, I thought of the relationship between these two buildings. The cathedral and the small house are not only a representation of the two coexistent local religions—Catholicism and Santeria—but also of the two sides of Cuba—one put in place for tourists and visitors and the other side of the city that one has to look further to appreciate: Cuba for Cubans. I’m by no means an expert on the subject, nor do I intend to sound like one, but from what I could observe, gather, and infer, Santeria is deeply rooted in Cuban society but not represented in the city’s formal infrastructure.

Te Estoy Mirando house

A few blocks later we made it to lunch in a local paladar. For many this was one of the best meals we had, and I agree. The fully renovated 1890s house had a phenomenal atmosphere with amazing works of art and top-of-the-line musicians, great food, and young, energetic waiters representative of a new generation of Cubans. The owner, a young engineer, came to greet us and to tell us about his paladar, a project he initiated with his wife three years ago. Today he supports over 18 local farmers by only buying local produce and hires students and cooks who love to innovate and rediscover Cuban cuisine. After a succulent lunch, we continued our walking trip of Havana. Now it was time for El Paseo del Prado, an elegant boulevard designed by Jean Claude Nicolas Forestier in 1772. Originally it was surrounded by theaters, mansions, clubs, cafes, and restaurants, some of which still exist in an excellent state of conservation.

Our lunch in a local paladar

After the Prado Boulevard, we visited a working-class neighborhood close to the Capitol and our hotel. Havana is full of contrasting architecture. Blocks of five-star hotels are surrounded by a larger number of dilapidated, impoverished blocks of literally crumbling housing. Interestingly, the two extreme realities cohabitate in peace with extremely low theft rates. The reason we walked into this underprivileged part of town (confusingly close to our part of town) was to look at some interesting examples of 20th-century domestic architecture, especially a couple of rare art nouveau houses Monty had spotted before. I must say, Monty knew no limits when it came to finding great architecture; our leader wasn’t restricted by a sense of scale and he was forgiving with the ungracious effects that time had on some buildings. He would share with us and talk with the same passion about the Bacardi headquarters or about a crumbling small Art Deco house in the middle of nowhere. I’m happy to report that this neighborhood and many of its houses were the cherries on the cake, the perfect closure to a day charged with magnificent architecture and history.

Susanne, David, Dan, Pat, Tim, Ryan and Julie listen to Monty explain the buildings surrounding El Paseo del Prado.

Art Nouveau houses in a working neighborhood in Havana

Right across the Art Nouveau houses, the group took pictures and took time to absorb the beauty of it without knowing that they made a pretty good picture themselves.

Day 4. Tuesday, December 4th, 2018. Spectacular Cuban Modernism Part I.

Today we incorporated a very distinguished guest to our cohort: architect and historian Eduardo Luis Rodriguez. Eduardo Luis is an internationally recognized expert, an outstanding scholar and a charming person whose smile, soft voice, and passion for Cuban architecture captivated us as soon as he started talking. We began our tour with the Solimar building, designed by Manuel Copado and built in 1944. The name of the building means “sun-and-sea” and Eduardo said that the sensuous shape of its balconies was a poetic reference to the waves. The seven story-high building is oddly out of scale in the middle-class neighborhood; this fact grants its upper floors an outstanding view of Havana and the sea.

Solimar building

View from the 6th floor of Solimar

Monty caught smiling in one of his favourite buildings in Havana

Moving away from Solimar, we drove to the Colegio de Arquitectos, the architect’s association, a 1944 elegant modernist building designed by Fernando de Zárraga and Mario Ezquiróz. I was personally impressed by the elegant tectonics of this building representing our guild.

The green and grey construction consists of a semi-basement and two floors occupied by offices, a library, a fencing room, an auditorium, study rooms, and a large entrance hall, which was the only space we were allowed access. In the lobby, we photographed the slim and elegant staircases while a nervous secretary appeared to wonder the reason for all this commotion.

Colegio de Arquitectos of Havana

Eduardo Luis explaining the Colegio de Arquitectos

Staircase inside the lobby

After hearing Eduardo Luis talk passionately about several buildings on that same block, we took our conversation to the bus while Juanito drove south to La Universidad de La Habana. The massive neoclassical complex built between 1906 and 1940 inspired by the Greek Parthenon and Columbia University is located on the Arostegui hill overlooking the Cuban sea. The complex has seven different entrances; the main one was monumentally conceived with an 88-step staircase topped with a bronze statue of Alma Mater created in 1919 by the Czech-American sculptor Mario Korbel.

Our group standing on the main entrance of Universidad de La Habana

Resting inside the University's Aula Magna

After visiting the University, we went for lunch in a local paladar called La Moraleja located in the El Vedado neighborhood inside a beautifully renovated eclectic house. What came next was one of the favorite parts of the trip for many of us: modernist Cuban houses. Our first visit was to the house of Guillermina de Soto Bonavĺa, built in 1957 by Mario Romañach. The modernist building, impeccably kept by its original owner, adapts Japanese and Corbusian concepts to the elements of the tropics. True to the research interests I walked to the back of the house hoping to find the domestic employee’s bedroom; there it was, transformed (like it usually is) into a storage room. Following conventional architectural patterns, it had been placed behind the kitchen, next to the service area and the posterior patio. What was interesting is that despite characteristic reduced dimensions and marginal location, the interior of the room complied with the rest of the house’s architectural language of wood louvers, brick, and cement. The tiny bedroom had a neat brick wall, wood, and tinted glass windows, indicative of the cohesiveness between the service area and the rest of the house.

Our group arriving at the Soto Bonavia Residence

Eduardo Luis with our host, Berta.

On the left the sliding doors are completely open, on the right they're open halfway. Jack, Julie and Victoria take pictures of the house and its amazing views.

It was time to move on to our second house call of the day, also in the El Vedado neighborhood, the Farfante Residence designed by Frank Martinez in 1955. This phenomenal house was conceived for two sisters living in independent units yet sharing some communal areas. Today the house is occupied by two families of the father (on top) and son (on the first floor) relatives of the original owners and proud guardians of this architectonic gem. Knowing the importance of the house, the current residents take exceptional care of the structure and the original furniture. The most impressive feature of these houses is how they adapt modernist concepts to the tropics with their strategic use of crossed ventilation to regulate interior temperatures. Wood and glass louvers, brise-soleil, sliding doors, terraces, and vegetation are critical architectonic elements to adapt to the Cuban weather. This house can be manually open almost entirely to become a galleria where the wind can blow freely, refreshing everyone inside. In this home, I asked about the domestic workers quarters and was told they had been repurposed as a mechanical shop. The owner pointed out an additional set of stairs in the back of the house behind the kitchen that used to go to the servants’ bedrooms. This space was not given the same aesthetic considerations as the rest of the house neither in the original materials nor in the posterior upkeep.

Cross ventilation is easy to regulate with these sliding wood doors still intact after more than five decades.

Service area with stairs leading to the servants’ quarters

To wrap up a wonderful day we visited a house designed for the Cuban painter Enrique Garcia Cabrera. The Art Deco home by Max Borges features two reliefs in the brilliant façade, one by Garcia Cabrera himself and another by one of his students, Manuel Rodulfo. The interior of the house has carefully kept all the original materials, furniture, and artwork and the artist’s large studio still displays his last unfinished work on the easel. The current residents of the house, a couple of intellectuals related to Monty, invited us for refreshments and a joyful evening of pleasant conversation.

Part of the group without host in the backyard of the Garcia Cabrera house

Garcia Cabrera's studio

Relief by Garcia Cabrera

Our group having a wonderful time

Day 5. Tuesday, December 5th, 2018. Spectacular Cuban Modernism part II.

Excited to see and hear Eduardo Luis again we arrived at our first visit of the day, the Hebrew Community Center by Aquiles Capablanca, built in 1951. Before the revolution, the Hebrew community in Havana used the main (and largest) part of the building for recreational purposes, social events, and administration. The almost hidden lateral section of the building—smaller, less monumental yet gracious and elegant—was, and continues to be, the synagogue with a large catenary arch that welcomes visitors with wide arms. Today, only this smaller section of the building belongs to the Jewish community as the other larger parallelepiped is the Bertold Brecht Cultural Center.

Interior Views of the Synagogue

Exterior facade of the Synagogue

Our next two scheduled visits were contrasting examples of architecture and life stories. First, an elegant yet extravagant pink Italian Renaissance palace that the sugar magnate Juan Pedro Baró built for his creole Anna-Karenina-type-of-love named Catalina Lasa, supposedly the most beautiful woman in Havana. Designed by Evelio Govantes and Félix Cabarrocas in 1927, the building was the first in Cuba to have interior Art Deco spaces designed by Rene Lalique, also the designer of Catalina Lasa’s mausoleum. Art Deco is only present inside the mansion as the product of deep infatuation with the style that came too late in the construction process.

Eclectic exterior of the Baro-Lasa residence

Eclectic interior of the Baro-Lasa residence

Art Deco interior of the Baro-Lasa residence

Next, we went to a very different home designed thirty years later for the de Schulthess family by Austrian-American architect Richard Neutra. Originally the house was commissioned by a Swiss banker to house his family of five in the upper-class neighborhood of Country Club, today known as Cuabanacan, in a 9,896-square-meter lot. De Schulthess contacted Neutra through a common friend who immediately accepted to build this house, writing to de Schulthess, “This project is not the beginning, but it is supposed to be a culminating event in my career at the service of human beings.”1 This house is a fascinating adaptation of Neutra’s iconic architecture to the Caribbean. Unlike most of Neutra’s projects, which have a steel structure, the de Schulthess residence is supported by a reinforced concrete structure following the standard local building techniques. Wood, concrete, and framed glass bring the exterior vegetation in and allow it to become part of the architecture. The extraordinary landscaping, an integral part of the global design, was planned by the world-famous Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. I knocked on the kitchen door and asked to see the kitchen and the back of the house; the answer was the same I receive everywhere, an incredulous “sure” followed by a “there’s not much to see here."

Given that this house is the official residence of the Swiss ambassador, the service area is fully functional and occupied by a large staff as originally intended. The spacious kitchen and service area are segregated from the rest of the house by a large white wall and a wood revolving door. Inside this area, there is a servants’ lounge with a tiny table to eat and a garden definitely not designed by Burle Marx. Also, I discovered a long hallway of doors pertaining to the servants’ bedrooms, comparable with the upstairs bedrooms’ hallway. The difference was the size of the hallway and its windows, and the lack of interior vegetation and elegant light fixtures on the bottom floor. After a cocktail courtesy of the Swiss ambassador’s chief of staff, we went for lunch in a restaurant by the sea where we sat on the upper floor terrace of a fully renovated house with an incredible aquatic view.

Our group with Eduardo Luis and staff from the Swiss Embassy

Interior of the de Schulthess home

Gardens of the de Schulthess home designed by Burle Marx

Kitchen door and interior of the large kitchen

Domestic servants eating area

Service are view from above

Servants bedroom

Family bedrooms

Lunch with a view

In the afternoon we fast-forwarded to contemporary Cuban architecture as we visited the house/studio of the wonderful female architect Vilma Bartolome. The project started as her home and evolved into an art and architecture gallery. According to Vilma herself, the two story, fully renovated house blends minimalism with elements of Cuban and tropical architecture such as vernacular materials, vegetation, and use of light and ventilation. Vilma is in charge of redesigning the important Linea Street in Havana and represents the talent, wisdom, and pride of contemporary Cuban artists. I feel privileged to have met her and her team.

Architect Vilma Bartolome

Vilma Bartolome's house

Day 6. Thursday, December 6th, 2018. Revolutionary Architecture

Our last day in Havana was devoted to education and revolution. We began by visiting the Centro Universitario Jose Antonio Echeverria (CUJAE). This colossal architectural work is considered the most important built after the revolution. CUJAE is an exemplary project that adapts brutalism to the local weather conditions by including local building and design traditions such as patios, long covered galleries, and shutters to regulate light and air flow. More than forty modernist buildings grouped in a 398,000-square-meter area house CUJAE’s faculties of architecture and eight engineering. The total complex includes classrooms, laboratories, conference rooms, libraries, workshops, warehouses, student housing, cafeterias, administration offices, sports facilities, and printing services. The main drawback of this polytechnic school is its isolated location and difficult, and expensive, access by public transportation. A student told me in the bathroom how one of her classmates couldn’t continue her architectural education because she couldn’t afford the bus fees to CUJAE.

One of CUJAE's patios

CUJAE

After CUJAE we made a quick stop in Las Ruinas Restaurant, a spectacular structure built around the ruins of an old sugar mill in the Lenin Park. Designed between 1969 and 1972 by Joaquin Galvan, the concrete and glass building gives the impression of a strong, brave guard protecting the delicate traces of a rich architectural past. Unfortunately, the building, which is currently underused as an unremarkable restaurant, suffered under the inexperienced hands of an uninformed interior designer who chose oversized crystal chandeliers and outdated ironwork handrails. Nevertheless, it is easy to distinguish Galvan’s intentions to the later thoughtless add-ons.

Las Ruinas Restaurant

We left Las Ruinas to visit what many (myself included) consider one of the best examples of Latin American architecture: The Escuela Nacional de Arte designed by Ricardo Porro, Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garratti between 1959 and 1964. Waiting for us at the entrance of the Art School was Universo Garcia Lorenzo, architect, university professor, and professional in charge of coordinating the renovation of the project since 1999. In the complex five schools are spread throughout the former Havana Country club golf course creating an ample campus devoted to arts.

Entrance to the fine arts school

First, we visited the fine arts school designed by Porro now fully occupied by exceptionally talented students. To enter, one has to choose between the three magnificent brick vaulted tunnels, walking through them is the perfect preamble to the outstanding interior. The fine art school is a conglomeration of smaller buildings connected by vaulted gallerias playfully unfolding around a large, uncovered courtyard. Inside the classrooms, the skylights in the gigantic domes are designed to shed zenithal light onto the works of art or live models.

Skylight in one of the fine art school's classrooms

Fine Art School's hallway

Fine art school's patio

Work of the art school's students

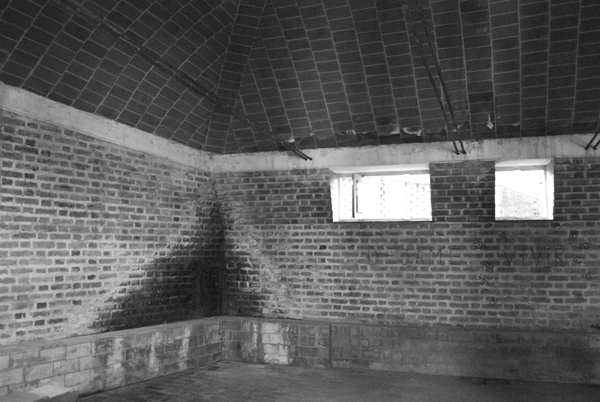

After the fine arts school, we walked to the second and last fully functional building: the school of modern dance, also designed by Porro. On our way, we passed by Garatti’s School of Music and Gottardi’s School of Drama, only halfway built and totally abandoned and empty except for a couple of squatter students who, in search for a quiet space to work, decided to reside there. One art student used the welding techniques learned in his sculpture course to build a zinc door for one of the empty classrooms.

A green door fashioned by an art student searching for a private space to work

After examining the abandoned structures, we walked to the dance school with a different atmosphere. The fully finished building was filled with dynamic young students chatting, stretching, and dancing to music everywhere. This building had a similar distribution to the fine arts school where classrooms are connected by ample vaulted hallways revolving around the main courtyard. Unlike the rest of the schools fully built in brick, here large, imposing, white walls contrast with the tile floor and roof, creating a more traditional effect. Lastly, we walk to the also abandoned school of ballet. For me, this was the best of the five buildings, even if dilapidated and only 80% completed. The game of shadows and lights created by the paper-thin non-continuous vaulted ceilings is moving and inspiring, like magic could be created here and nowhere else. It’s easy to imagine ballerinas pirouetting under this light, music filling the air around, and black and pink leotards adorning the grassy hills. With a perfect sunset, we say goodbye to this architectural tragedy, hoping that Universo finds a way to save it, to guard it against the inclement effects of time and nature. Goodbye Arts School, goodbye Havana!