On June 2, 2017, a few days before Frank Lloyd Wright’s 150th birth anniversary, two dozen historians, professors, curators and architecture-enthusiasts were offered the exclusive opportunity to attend a special preview of the major exhibition organized by MoMA for the occasion. As the lucky recipient of the SAH fellowship, I was granted the privilege to attend the event, which included an in-depth insight over the management and development of the show.

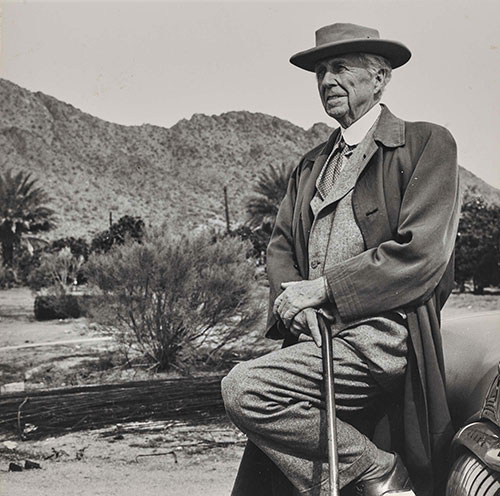

A historic photo of Frank Lloyd Wright. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.

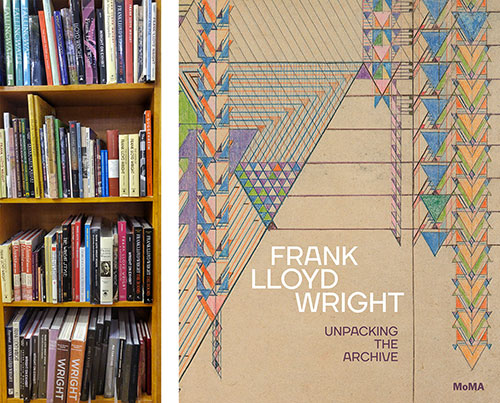

As a first-time visitor to the US, the opportunity granted by the fellowship proved an especially significant experience for me, both as a first-hand encounter with the culture and environment in which FLW’s practice developed and in raising my awareness about the reverence still surrounding his figure there. Walking into a local bookshop before the Study Day, I faced entire shelves brimming with monographs about his person and work, making me query how they have managed to mount a new and original show about such a well-known and cherished personality.

Left: Monographs about Frank Lloyd Wright in a New York bookshop. Photo by the author. Right: the cover of the exhibition catalogue (Barry Bergdoll and Jennifer Gray, Frank Lloyd Wright: unpacking the Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2017).

What to do new? How to offer new critical insights after so much has already been said and written? How to manage a project satisfying both historians and the general public?

At the Study Day, co-curators Barry Bergdoll and Jennifer Gray offer an exhaustive introduction, describing their work with FLW archival materials and explaining how the avoidance of a monographic approach was one of their key concerns.

Their presentation makes clear that rather than the architect, the protagonist of the exhibition is the archive itself. As suggested by the subtitle “unpacking the archive,” they developed a thematic show centered on materials derived from the recent acquisition of FLW’s archive by MoMA and Columbia University’s Avery Library. Each section of the show has been curated by a different scholar working on the archive materials and has been developed around documents never—or rarely—studied and exhibited before. The conceptual framework is provided by the historians’ confrontation with these materials and their effort of drawing out of them new questions and critical insights; as a result, the show seeks to investigate new topics and to disclose the archive’s potential both historically and in relation to contemporary debate.

The group found its way to the gallery space through the newly opened Bauhaus staircase at MoMA. Photo by the author.

After the introduction, the group moves towards the third floor where we access the newly renovated gallery space housing the exhibition. Once past the black curtain still denying access to the wide public, we are confronted with a large exhibition space. The entrance point offers glimpses of various rooms, letting us free to explore and focus on any piece capturing our attention. There is no clear path to follow: the fluid relationships between the sections reflect the composite nature of the exhibition, where the different contributions relate to one another in an open dialogue. Video presentations by the curators introduce each section and the echo of their voices within the gallery aptly reflects their collective engagement in building the show.

The Gallery Space as seen from the entrance. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

In our case are curators in person to introduce one by one the twelve sections in which the exhibition is divided. We slowly walk across all of them but not strictly adhering to their suggested sequence since each room can be regarded as a small, self-sufficient entity, related but at the same time independent from the others.

The curators take turns presenting their selection of materials and their efforts in building a meaningful conceptual and visual narrative out of them. Their insights reveal the richness of the original archive materials and their struggle in selecting just few, essential pieces out of the many thousands they originally worked on.

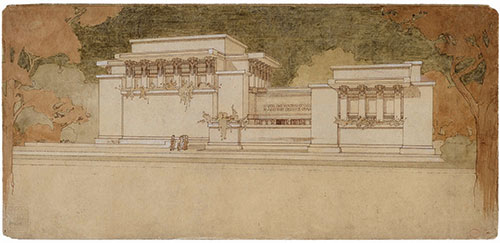

Frank Lloyd Wright, Perspective drawing of Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1905-08. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.

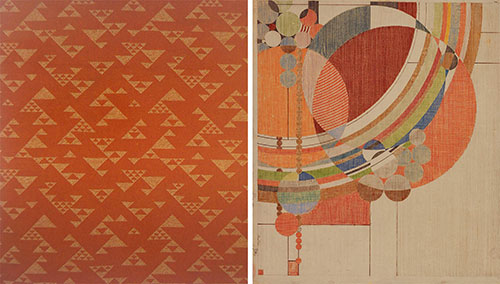

I am specially surprised by the great variety of media presented: urban plans stand alongside tableware but each piece is contextualized as part of a coherent and unitary project. The abundance of architectural drawings and sketches reveals FLW’s dedication to architecture as chief discipline; but the rich variety of photos, textiles, furniture and other media disclose his approach and inventiveness in all its manifestations, in a fascinating interaction of architectural and non-architectural materials, of pieces conceived for display and private records.

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright, upholstery fabric destined to the Imperial hotel, Tokyo, 1913-23. Silk and Viscose. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright, March Balloons. 1955. Colored pencil on paper. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.

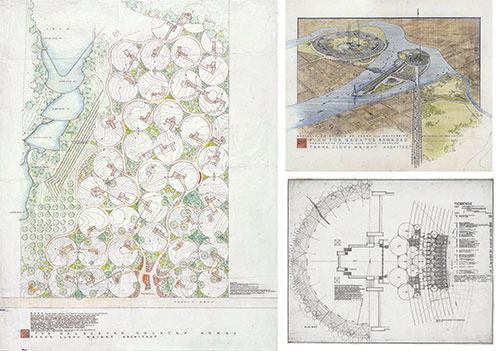

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright, Site Plan of Galesburg Country Homes, Galesburg, Michigan, 1946-49. Top Right: Frank Lloyd Wright, Aerial perspective of Greater Baghdad Project, 1957. Bottom Right: Frank Lloyd Wright, Darwin Martin House, Buffalo, New York, 1903-06. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.

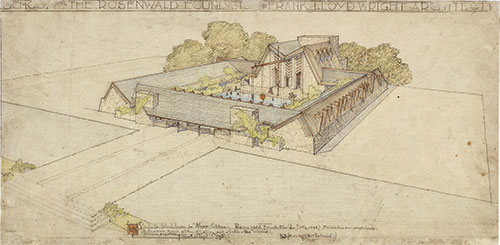

Although the colors, the geometries, and the Japanese-inspired drawing style unmistakably bears the architect’s distinctive touch, I found myself facing mostly unfamiliar objects and documents: as forecasted by curators, there is little room for FLW’s best known projects, and many sections actually deal with the re-assessment of minor works. This is the case of the Nakoma Country Club or of the Rosenwald School, whose analysis forms the starting point for addressing issues of social, racial, and cultural nature. Scantily considered in the ‘official’ FLW historiography, these projects can be re-evaluated nowadays as stimulating examples of how the architect confronted respectively the culture and visual imagery of native Americans and the educational programs destined to the African-American community.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Perspective drawing of Rosenwald Foundation School, Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Virginia, 1928. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.

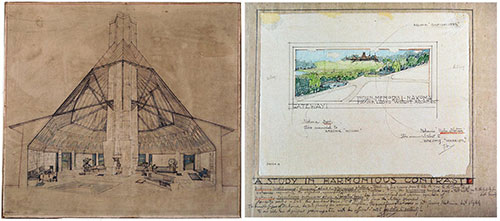

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright, Perspective drawing of the Interior of the Nakoma Country Club, Madison, Wisconsin, Project, 1923-24. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright, Perspective drawing of the Nakoma Memorial Gateway, Madison, Wisconsin, Project, 1924.

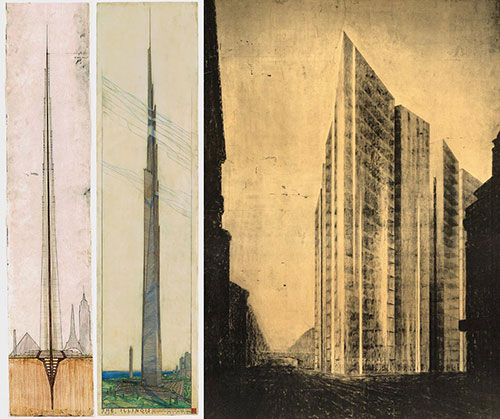

The issue of fame and the role of the media is investigated in the latest sections and notably in the one devoted to the mile-high skyscraper presented by FLW in 1956. In the room, the huge and elongated drawings of this utopian project stand alongside the famous perspective of Mies’ Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper as a visual statement of the adjoining of FLW’s and Mies’ archives in the same institution. The juxtaposition of these pieces and the skillful usage of the exhibition space provide inspiring suggestions for future study and research.

A snapshot from the TV Show ‘What’s my line?’ defining FLW “World Famous Architect”. June 3rd, 1956.

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright, Bottom segment of the section drawing for the Mile-High Illinois, Chicago, Project, 1956. Center: Frank Lloyd Wright, the 8 ft. high perspective drawing for the Mile-High Illinois, Chicago, Project, 1956. © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale.Right: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Perpsective Drawing of the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper, Berlin-Mitte, Germany, Project 1921.

The juxtaposition of Mies’ Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper and FLW’s Mile-High skyscraper within the gallery. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

Indeed, by the end of the day, this exhibition must be regarded as a starting point rather than a conclusion. Despite the richness of insights offered, I found myself bubbling with plenty of new questions and ideas and notably wondering about all those pieces that for various reasons could not find their way to the gallery space. What the group and the public are presented with is nothing but the tip of the iceberg of a heritage still awaiting to be fully discovered and debated. Notwithstanding the over 400 pieces exhibited, I feel my curiosity stimulated rather than just satisfied from what I saw, and it is exactly with this pleasant feeling of an open-ending that in the evening I eventually walk out of the Museum.

Federica Mentasti is a scientific assistant and Ph.D. candidate by the Chair for History and Theory of Architecture at ETH, Zürich. She received a bachelor's degree in architectural studies from Accademia di Architettura Mendrisio (Switzerland, 2014) and a master's degree in architectural history and theory from the University of Edinburgh (Scotland, 2016) with a thesis about Japanese influences on Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Practicing photographer for over five years, her prospective research seeks to investigate the relationships between architecture and photography.