Introduction

“Architectural Layers of a Southeast Asian Region”—from the moment the tour began the title of our seminar rang true, as we uncovered the layers of cultural influences, political events and historical shifts that shape the current architectural landscape of Vietnam. The modern histories of French colonialism, the communist revolution, and the subsequent war with America often overshadow the fact that Vietnam was ruled by China for nearly 1,000 years. This sustained relationship with Vietnam’s northern neighbor is evident today in the influence of Taoism in city planning, traditions of ancestor worship carried out at Buddhist temples, and the architectural styles of many of the extant structures built by Vietnamese royalty. The Nguyen Family, who unified the country in the early 19th century, modeled their rule on the Qing Dynasty in China. The Nguyen mausoleums, temples, and the Imperial City in Hue are covered with reliefs and mosaics in Chinese script, illegible to most Vietnamese today. French colonization in the second half of the 19th century brought with it the neoclassicism rampant at international expositions of the time, the Haussamannization of city streets, innovative attempts at developing an integrated European-Indochinese style, and, eventually, modernism. Ho Chi Minh City’s long history as a port city in the Mekong Delta is the basis for its current cosmopolitanism, seen in the ethnic Chinese markets, southern Indian Hindu temples, neoclassical hotels, Art Nouveau shop houses, modernist apartment blocks and contemporary skyscrapers that dot the city. It seemed only natural that many of our conversations turned to the topic of how to effectively teach courses on world architecture, as many of the world’s architectural forms, styles and materials seem to exist in this long, narrow strip of land on the coast of Southeast Asia.

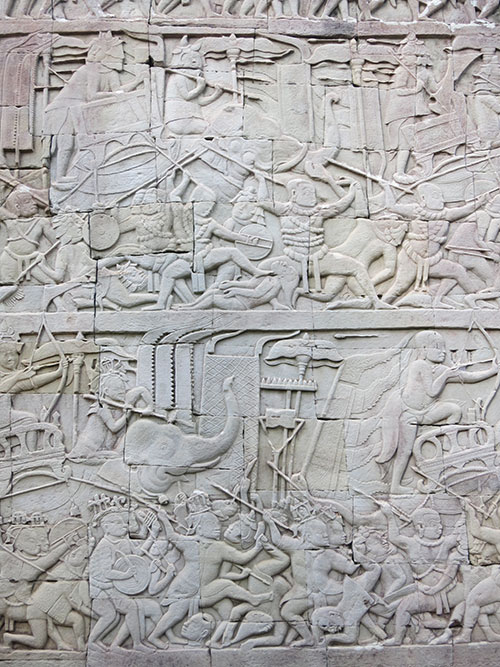

The theme of layers continued in Cambodia, where we spent three days in the Angkor Archaeological Park. The mountain temples built by the Khmer Empire in the 10th-13th centuries are literally made up of layers—stones cut to fit together and corbelled to reach immense heights. The walls of these sprawling temples, monasteries, and fortifications are layered with registers of bas-reliefs that picture deities, stories from Hindu mythology, the history of the Khmer people, and decorative motifs taken from nature. At times, these ancient structures are layered in with the natural landscape; sponge trees weave in and out of the ruins at Ta Prohm and Hindu rock carvings peak out from under the river water near the mountain Phnom Kulen. My own research focuses on the myriad ways in which ruins have been interpreted, repurposed, and visualized to construct varied narratives of history. From the French colonialists to the Khmer Rouge, the ruins of Angkor also have a layered history of adaptations, co-optations, and reinventions. Today, they continue to be reconceived by the many countries that lead and fund preservation and restoration projects in the region. Angkor confirmed for me that it is precisely the layered and at times incoherent nature of ruins that allows for the multiplicity of meanings and histories that they generate.

Day 1: Hanoi, Vietnam

After a late-night arrival in Hanoi, our group met bright and early the morning of December 3rd in the lobby of the Silk Path Hotel for introductions and an overview of the coming ten days. Professor Hazel Hahn briefed us on the many exciting sites that lay ahead, and our local guide, Duk, provided a tutorial on survival tips in Vietnam. Duk’s most invaluable piece of advice: cross the streets slow and steady—“hand-in-hand like sticky rice!”—in order to avoid getting squished by one of the five million motorbikes buzzing throughout the city of Hanoi. This advice rang true for Hue and Ho Chi Minh City as well. It is impressive to watch these things speed around, carrying baskets of flowers, entire appliances, families of five—you name it!

Fig. 1: Doan Mon Gate, one of the main entrances to the Forbidden City in Hanoi.

Fig. 2: The original dragon steps from the Forbidden City. The dragon is one of the four sacred animals in Vietnam along with the unicorn, phoenix and tortoise.

Soon, we were off to the first site—The Central Sector of the Imperial Citadel of Thang Long, the enclosure that was built to house the Forbidden City when Hanoi was founded as the capital of Dai Viet in 1010 (Fig. 1). The citadel was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site exactly ten centuries later in 2010. Although the site dates from the 11th century, it has been rebuilt and repurposed many times, and most of the extant buildings date from the 19th and 20th centuries. Given my interest in ruins, it was impressive to see how the remnants of former structures had been incorporated into newer ones. For example, the stone base of the Doan Mon Gate dates from the sixteenth century, as do the palatial dragon steps that sit across a small plaza from the military barracks constructed by the French colonial government in 1897 (Fig. 2). This same building became the military headquarters for the north during the Vietnam War (or the American War, as it is known in Vietnam), and the General Command Headquarter Military Operations Bunker was built underneath it and occupied from 1965-1973. The bunker connects to an underground passageway leading to a building known as D67, another military headquarters built on the site in—you guessed it—1967. In this way, the citadel represents centuries of political history in Vietnam—a fascinating and appropriate location to begin our introduction to Hanoi and Vietnamese history.

After lunch in an old colonial villa we made our way to the Presidential Palace Grounds, another complex with layers of political history that includes the Presidential Palace, the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, Ho Chi Minh’s stilt house, and the One-Pillar Pagoda. The Presidential Palace, formerly the Palace of the Governor-General of Indochina, was constructed in 1906 by the French government. The largest building Hanoi at the time of its construction, it is a Beaux-Arts aristocratic residence that was meant to impress the colonized subject. Professor Hahn pointed out stylistic commonalities that it shares with many of the neoclassical buildings constructed for the 1900 International Expo held in Paris, such as the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais.

Fig. 3: The wooden stilt house where Communist revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh lived from 1958-1969

The Communist revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), who is still warmly referred to as “Uncle Ho,” refused to live in the luxurious palace after Vietnam gained its independence from the French in 1954. Instead, he had a wooden stilt house built nearby, where he lived from 1958 until his death in 1969 (Fig. 3). The house is based on the vernacular architecture of the hill tribe peoples of Vietnam, raised on stilts to provide safety from wildlife. After his death Uncle Ho’s body was embalmed, and he can still be visited in the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, a stark, square Soviet-style building that sits on the vast parade grounds of Independence Road (Fig. 4) The stone walls of the mausoleum and the flora and fauna that surround it come from all over the country, a symbolic gesture to Ho Chi Minh’s status as the “Father of Vietnam.”

Fig. 4: The Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, where we were lucky to witness the changing of the guards.

The final site that we visited on the grounds of the Presidential Palace was the One-Pillar Pagoda, so-called for the small temple-like structure held up by one large white pillar (Fig. 5). The bracketing system that connects the structure to the pillar is particularly impressive. The roof, with its highly pitched ends, is meant to resemble a lotus flower. Originally built in the 11th century, this was the oldest Buddhist structure in Vietnam until it was destroyed by the French. The current replica dates to 1954.

Fig. 5: The One-Pillar Pagoda

In Focus: The Work of Ernest Hébrard

In 1923, the French architect and urban planner Ernest Hébrard was appointed as the head of the Indochina Architecture and Town Planning Service. Although much of it went unrealized, Hébrard mapped about a large-scale urban planning project for Hanoi. During our first two days in Vietnam we were able to visit four of the five extant Hébrard buildings in Hanoi. All four structures attest to Hébrard’s sustained effort to formulate an integrated French-Indochinese style of architecture.

On our first day we visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (formerly the Direction des Finance), built from 1925-27. Hybrid design elements can be seen in the white lotus-capped gate posts, as well as in Hébrard’s Art Deco take on the interlaced design of the Asian swastika in between the windows on the building’s top floor. According to Professor Hahn, Hébrard’s desire to successfully incorporate both Vietnamese and French elements in a single design was not appreciated by the French authorities, who would have preferred a more purely European display of power.

Fig. 6: A detail of the bell tower of Cua Bac Church

Nearby, Hébrard’s Cua Bac Church dates to 1925 (Fig. 6). It is the largest church in Hanoi and has some wonderful Art Deco design elements. I was impressed by the large rose windows as well as smaller details, such as the sconces in the chancel. Duk was quick to point out the incorporation of local flora and fauna like the bonsai trees outside, which seem to make this a distinctly Vietnamese church. The use of color was also striking. We began to notice that many of the buildings we encountered had been painted in a bright yellow-gold, the color of authority and power. This was true of the Cua Bac Church, but the transition to the interior revealed brilliant white walls with accents of blue and yellow in the stained-glass windows. It made for a peaceful and calming atmosphere in contrast to the motorbikes buzzing outside (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: The nave of Cua Bac Church. Notice the geometric designs that line the upper register.

The second day took us to the Vietnam National Museum of History, constructed from 1926-1931. Originally, this museum was built to display the collection of the ̀Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, or the Institute of Far Eastern Studies, established by the French colonial government to study ancient Asian civilizations, particularly the Khmer. Professor Hahn considers this to be Hébrard’s most successful incorporation of eastern and western architectural styles, and our group was equally impressed. For the design of this museum, Hébrard conducted a thorough study of building types from different Asian countries. However, rather than create a pastiche, he attempted a more cohesive and, therefore, innovative design. The façade emphasizes the horizontal orientation of the building, with graphic motifs in variously raised and sunken sections that create patterns of light and shadow across the surface (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: A detail of the façade of the main gallery at the Vietnam National Museum of History

The final Hébrard building that we visited was the Hanoi University of Pharmacy (1926), originally the University of Indochina. This was the first university built in French Indochina, and it remains one of the most important universities in Vietnam today. Interestingly, there is a great deal of continuity in terms of the function of colonial-era buildings; schools remain schools, hospitals remain hospitals, and many ministries continue to be occupied by the current government.

In Focus: Temples and Taoist Planning

Religion in Vietnam is a mixture of various traditions, including Buddhism, Taoism, ancestor worship, and various forms of animism. Geomancy — the auspicious design and placement of buildings and spaces — comes from the Taoist tradition, and we encountered examples of its implementation, along with that of feng shui, in Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City. For example, in most cities temples were built in the four cardinal directions to protect the area from harmful forces. In Hanoi, we were able to visit the North and the East Temples (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: The main gate to Quan Thanh (North Gate) Temple

Day 2: Hanoi, Vietnam

Our second day in Hanoi began with a walking tour of the French Quarter—the area that was planned by the French colonial government in a Second Empire/Third Republic manner with wide boulevards lined with trees. Today, the architecture varies quite a bit, but the occasional colonial villa continues to recalls the origins of the area. Some historic sites in the French Quarter include: the Clinique Building, a 1920s Art Deco hospital; the First Mortgage Bank from 1930; the 1942 Central Post Office, now an annex to the post office; the State Bank of Vietnam, which was designed by Georges André Trové in 1930 and incorporates Asian motifs into an otherwise austere design; and the lovely villa, Casa Italia. On our tour we were reminded again of the general tendency for extant colonial-era buildings to continue to serve their original functions.

Many buildings in the French Quarter are known for their metalwork done by Vietnamese artisans. The Hotel Sofitel Metropole is a massive hotel from 1901 that sits across from the Ministry of Labor. It was recently renovated and exudes an air of colonial nostalgia. The awning supports outside the grand entrances and café display exquisite metalwork design that reminded me of the wrought iron balconies and window grating seen throughout the French Quarter in my native home of New Orleans. Down the street from the hotel lies the former Residence Superior of Tonkin (1919). Ho Chi Minh worked from here in 1945-6, and today it serves as a government guesthouse. The Art Nouveau influence is clear in the metalwork design on the gates to the residence (Fig. 10). Indeed, Professor Hahn pointed out similarities to the famed metropolitan subway entrances in Paris that were built only a few years prior to the Residence.

Fig. 10: The entrance gate to the former Residence Superior of Tonkin

Fig. 11: The roundabout in front of the Opera House, designed by Architects Lagisquet et Harlay

From here, the walk to the Hanoi Opera House (1908-16) made clear the influence of Haussmannian urban planning in the French Quarter of Hanoi (Fig. 11). Seven broad avenues radiate out from this central monumental structure. The roundabout in front of the main entrance made for a visually impressive approach, but a rather scary street crossing!

In the afternoon, we made our way to the Old Quarter of Hanoi. This area was developed as the city’s primary commercial center beginning in the 17th century when people began to move from the countryside to the capital, bringing with them their local trades and religions. The Old Quarter is called “The Area of Thirty-Six Streets,” where each street was devoted to a different trade. Today, you can still see street signs, such as “Sugar Street,” that indicate the history of the area. Duk clarified that there are actually more than thirty-six streets, but since nine is a lucky number in Vietnam (and 3 + 6 = 9), it came to be called the “Area of Thirty-Six Streets.” The Old Quarter is considered a part of Hanoi’s ancient city, and the streets continue to reflect its original organic development. This is where the first modern market was built in 1906. Today, the Don Xuan Market still has three of its original five stands at the entrance, marked by broad arches linked with pillars. The French did little to intervene in the planning of the Old Quarter during the colonial period, and it maintains a lively, bustling atmosphere — attracting tourists, but not giving over much infrastructure to the industry (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Haircuts, coffee, and motorbikes — a typical sidewalk scene in the Old Quarter of Hanoi

My own research deals with the modern history of redevelopment in Japanese cities, where preservation is not a priority and urban buildings have an average lifespan of twenty years. We learned that the economic history of modern Vietnam, while difficult for the Vietnamese people, had favorable results for the preservation of historic sites and structures. The economy suffered after the American War, and there was little money to renovate or build anything new in cities such as Hanoi. The city’s important architectural heritage was recognized with the growth of tourism in the 1990s, leading to grassroots preservation movements in the Old Quarter and the French Quarter.

A wonderful place to learn about the history of living conditions in the Old Quarter is the Ma Mai Heritage House from the late 19th century (Fig. 13). It is a typical merchant’s house, a long and narrow space that would have had a shop in the front with the living quarters in the back. These so-called “tube houses” could be as narrow as two meters and as long as seventy meters with the building expanding according to the growth of the family’s wealth. As you move back through the house, you come across multiple courtyards that allow for an abundance of natural light. Having lived in New York and Tokyo, the space seemed luxurious by most urban living standards today — that was until I learned that as many as fifty people could have been crammed into a single house at a time. In 1954, those peasants who had contributed to the independence movement were invited to live in houses in Hanoi, leading to an incredible amount of overcrowding in the cities that lasted until the 1990s.

Fig. 13: Looking through the layers of open-air courtyards and interior spaces in the Ma Mai Heritage House

In Focus: Housing in Hanoi

Besides the Ma Mai Heritage House in the Old Quarter, we had two other opportunities to learn about housing in Hanoi. At the end of our second day, we visited the House of Le Phuoc Anh, a young Vietnamese architect trained in France. Anh comes from a lineage of architects. In fact, his grandfather collaborated on the design for the Central Post Office that we saw earlier in the day. He inherited his family’s colonial villa in the French Quarter and built a contemporary house across the ally from it. I think we all wanted to live there! It is modern in its materiality—the way that steel and glass are employed to create visual points of interest while also serving important functions, as in the suspended walkway that leads to his studio above the living room. But, the house also maintains a connection to many of the other buildings that we saw in Hanoi, particularly in its vertical orientation; multiple sets of stairs and layers led to a delightful rooftop garden.

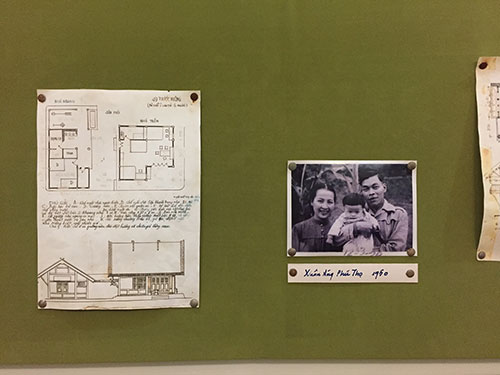

Today, Anh’s family occupies both homes. However, because of the housing shortage in Hanoi the government requires him to share the first floor of the villa with another family. Anh’s theoretical interests concern issues of identity and urban planning. He believes that identity needs to be considered more broadly without recourse to nostalgia. It is clear that his own family identity is sacred to Anh, as the walls of his colonial villa are covered with photographs and drawings by his grandfather (Fig. 14). In his work, Anh thinks about the relationship between identity and space in connection to the widespread redevelopment occurring throughout Hanoi today.

Fig. 14: A piece of Anh’s homage to his architectural heritage

Fig. 15: Apartment blocks and clean streets in the gated community, Ciptura International City

Before departing Hanoi, we made an early morning visit to one example of such redevelopment: Ciputra International City (Fig. 15). Ciputra is an example of one of many new planned communities being built by foreign corporations throughout Vietnam. It is a gated development with uniform housing types in the form of single-family villas and tall apartment blocks. The architectural styles are European-inspired, but the narrow, vertical orientation of the villas continues the tradition of the “tube” housing that we experienced in the Old Quarter. It is expensive to live here, but the community includes many modern amenities. The complex felt nothing like the rest of Hanoi: it was quiet and clean; there were no motorbikes in sight; and it lacked the spectrum of color that makes the streets of Hanoi so enticing. With the overcrowding of residences in the city after 1954, people in Hanoi brought their daily activities out onto the sidewalk, and this is still where people eat, children play, and shopkeepers or food vendors conduct business. For this reason, we were all delighted to see a woman take to the sidewalk for her early morning meditation and stretching routine in the otherwise reserved atmosphere of Ciputra.

Days 3 & 4: Hue, Vietnam

In Focus: Imperial Hue

After visiting Ciptura International City our group took a quick flight to Hue in central Vietnam, where we spent two days learning about Vietnam’s own imperial history. The Nguyen Family united the country under one rule in 1802 and established an imperial capital in Hue. The French allowed the royal family to remain in place as figureheads during the colonial period, but in 1945 the last king, Bao Dai, was forced to abdicate to the communist authorities. The city was flattened in the war with the French in 1947 and again in 1968. Afterwards, the communist regime considered the city an embarrassment, a reminder of the country’s feudal past, and those historic sites that did remain from the former imperial city fell into further disrepair. Preservation efforts began in the 1980s and picked up significantly after the city’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. This history colored our experience of the sites as we encountered buildings in various stages of rehabilitation.

On our first day in Hue we visited the historic Imperial City. This compound consists of three concentric areas: the surrounding enclosure and citadel, the Imperial City, and the Forbidden City in the center. The enclosure is made up of a 10-km stone wall and surrounding moat with a massive flagpole in the center of the southern wall. The flag sits on top of three foundations, a Confucian representation of the unity of heaven, earth, and man. Just inside the wall lies a large square for ceremonial gatherings with the great South Gate, or the Phoenix Pavilion, to the north (Fig. 16). This is where the king addressed the people twice a year: first, to announce the results of the civil service examinations; and again to commemorate the first day of the season for rice cultivation. As the public face of the king and his authority, this is a decidedly monumental structure. As with the flagpole, the pavilion sits on a series of three foundations and consists of the central gate with two flanking wings that house ceremonial bells and drums. The general plan has connections to Buddhist structures (think of the Byōdōin in Uji, Japan), and from above it resembles a phoenix with outstretched wings.

Fig. 16: Our group heading toward the immense South Gate

After passing through the Pavilion, we encountered the Thai Hoa Palace, also known as the Hall of Supreme Harmony. It was the last building to be completed within the citadel in 1833, and it was the only building in the compound to survive both wars intact. This is where imperial coronations took place, and the amazing red lacquered columns with images of dragons and clouds reflect its ceremonial importance.

The four corners of the Imperial City served different functions, with the west side designated for religious purposes and the east for entertainment. In the southwest quadrant we encountered temples dedicated to the royal family’s ancestors with massive bronze urns for each of the thirteen Nguyen kings. The urns are decorated with images of different natural and cultural features of Vietnam, creating a kind of encyclopedia of the country’s achievements (Fig. 17). Behind the urns sits a three-story pagoda dedicated to the Nguyen ancestors, the tallest structure in the entire Imperial City. The northwest quadrant of the Imperial City was designated for the Queen Mother, the northeast for entertainment with libraries and a royal theater, and the southeast for administrative purposes. Finally, in the center of the complex lies the Forbidden City. Much of this area is still in ruins, but it is where the daily activities of the king, royal family, and concubines occurred.

Fig. 17: One of the nine bronze-cast dynastic urns depicting various flora and fauna of Vietnam

In Focus: The Royal Mausoleums of Hue

While in Hue, we visited four of the seven mausoleums built by and for the kings of the Nguyen Dynasty. Duk explained that although these complexes function mainly as tombs, we should not think of them as spaces for mourning. Most of the mausoleums were constructed during the king’s lifetime, and many were even used by him as a kind of second palace before his death. After his death and entombment, his concubines moved to the mausoleum to tend to the tomb and accompanying temple, and, indeed, we encountered many signs of the belief in a luxurious afterlife. I must admit that when I first saw the schedule, I thought that four mausoleums seemed like a bit much. However, I quickly realized that while there are some fundamental similarities between the sites, no two of these mausoleums are alike. They each differ in layout and decor, a reflection of the kings’ individual personalities. They also differ in terms of their material condition; while some had seen recent repairs and restoration, others were in a state of complete disrepair. It was fascinating to be able to observe these complexes in various states of ruin and splendor.

We began our first day in Hue at the Mausoleum of Minh Mang. Minh Mang was the second king of the Nguyen Dynasty and a diehard Confucian. The king and his geomancers spent fourteen years searching for the most auspicious site for his tomb! Construction began in 1840, just in time for his death in 1841. It took three years and 10,000 men to build the fourteen structures at the site, which is spread out over 14 hectares. Together, the landscape and the buildings mimic the shape of the human body to reflect the Confucian principle of the harmony between the social and natural orders. The primary structures are laid out symmetrically on a north-south axis. They consist of:

1) The south gate and main plaza. The gate has three arched entryways. The central door is reserved for the king, and thus it has only been opened once when his body entered the precincts for his entombment. This pattern is repeated throughout the complex in the other buildings and gates. The plaza that follows the main gate is flanked by stone statues of elephants, horses, civil servants, and military servants, permanently standing guard, ready to serve the king in the afterlife (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18: A stone statue of a military servant guarding the Mausoleum of Minh Mang

2) An open-air structure to house the stone stele that records the biography of the king. In the case of Minh Mang, the stone came from the area of Vietnam where we was born. Chinese script was used for official documentation.

3) The temple for the continuing worship of the king (Fig. 19). A stone dragon staircase (with five steps for the five elements of the universe) and a gate lead to the temple where two small thrones are housed for the king and queen. A table sits in front for the presentation of offerings, and the interior is decorated with scenes of the four seasons and the four sacred animals — the dragon, unicorn, phoenix and tortoise.

Fig. 19: The façade of the temple dedicated to Minh Mang

Fig. 20: The last pavilion before the causeway that leads to the hill where Minh Mang is entombed

Fig. 21: The dragon staircase leading to the closed tomb of Minh Mang

4) The tomb itself (Fig. 20). After another series of gates and steps, we crossed a man-made lake to a hill in which the king is entombed (Fig. 21).

Ming Mang’s tomb is where we first encountered the “broken ceramics” that cover official buildings in Vietnam. This technique is comprised mainly of blue and white mismatched ceramics pieced together in a decorative mosaic on the exterior and interior of buildings. I found it mesmerizing. While the imagery is often repeated (for example, the four sacred animals or images of the four seasons), the execution differs at each site depending on the shapes and sizes of the broken pieces available to the artisan. I have never seen anything like it in other parts of Asia.

On our second day in Hue we visited three other royal mausoleums. First up: The Mausoleum of Tu Duc. Tu Duc ruled from 1847-1883, and he is considered the most learned of the Nguyen kings. It is said that his tomb, which is strikingly different from that of Minh Mang, reflects his poetic nature. In fact, the mausoleum was planned and built while Tu Duc was still alive, so he made use of it as a second palace—hunting and fishing, composing poetry, drinking tea, and meditating on the grounds. Instead of an axial plan, Tu Duc opted for an asymmetrical layout. After entering, we encountered a small man-made lake with a boat dock, tea pavilion, and small island in the center. To the left of this, a grand staircase led to the entrance gate to the temple, a beautifully carved wooden structure where Tu Duc would have stayed when he was visiting. After his death, his belongings were put on display here. Upon exiting the temple, we followed a meandering walkway along a man-made river to the burial area. This included the requisite plaza with the stone statues, the stele house with the biography of the king, two tall columns marking the site, and, finally, the tomb itself (Fig. 22). We could actually see the tomb this time — a simple square stone structure positioned in the middle of a circular enclosure. The curvature of the walkways, foundations, and water features served as a pleasant contrast to the rectilinear shapes of the buildings. Professor Hahn explained that while Tu Duc adopted a less literal interpretation of Confucian principles, he nonetheless managed to harmonize the buildings with the natural world around them. For example, the rounded foundations echo the hills that seem to hug the entire site; hence, the lyricism that people speak of in relation to the Mausoleum of Tu Duc (Fig. 23).

Fig. 22: A view from the gateway to the tomb area looking back at the stele house

Fig. 23: A detail of broken ceramics on a small wall built to block evil spirits from entering the tomb area.

Next, we visited the Mausoleum of Khai Dinh, smaller in size but BIG in personality. To say that Khai Dinh had expensive taste is an understatement. To build his tomb, he increased taxation by 30%. With ceramics and porcelain imported from other Asian countries and concrete and slate from France, it was the most expensive royal tomb to build, and it took eleven years to complete. It was constructed on top of the slope of a tall hill. The lack of a water feature combined with the influence of French Baroque architecture give this complex a heavy atmosphere. Having spent time in France, Khai Dinh was influenced by European notions of death. Thus, while the other two tombs that we had visited previously placed an emphasis on the life of the king, the exterior of this mausoleum felt more like a solemn memorial. The approach takes you up 127 steps, passing by the stone statues, stele house, and gates at separate intervals (Fig. 24) The interior of the mausoleum is dripping in ceramics and porcelain applied in the broken ceramic technique to the walls, ceiling, altar, and canopy that covers the tomb. A bronze life-size statue of Khai Dinh sits at the center of the complex above his tomb, a sun-like structure radiating behind him and motifs of the four seasons decorating the walls of each corner of the room (Fig. 25). Here, he has positioned himself at the center of time and space. While the heavy-handedness of the decoration gave it the feel of a nineteenth-century palace, the sinuous cloud and dragon motif painted overhead, the broken ceramics and Chinese characters made it hard to forget that we were in Vietnam.

Fig. 24: The final set of stairs leading up to the Baroque mausoleum of Khai Dinh.

Fig. 25: The bronze statue of Khai Dinh seated below a 1-ton canopy

Our final stop, the Mausoleum of Thieu Tri, could not have been more different in terms of style and material state. Thieu Tri was the third emperor in the Nguyen Dynasty, and the layout of his complex was similar to Minh Mang’s mausoleum in its adherence to Confucian principles. The temple and tomb are side-by-side instead of aligned in a single axis, each with their own north-south orientation. Thieu Tri died in 1847, and he requested that his mausoleum be constructed in a convenient location with the minimal number of buildings so as to save the national budget. It was completed in ten months. This site certainly felt more restrained, not only because of the understated approach, but also because of the general state of disrepair in which we found the mausoleum. The ceramics here had been broken twice, as former decorative pieces littered the ground around the structures that we passed through (Fig. 26). Conservation efforts are just beginning, and so it will be interesting to see just how much the complex changes as it is cleaned up.

Fig. 26: The ruins of former structures at the Mausoleum of Thieu Tri with the stele house in the background

Days 5, 6 & 7: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

In Focus: Redevelopment and Preservation in Ho Chi Minh City

After departing Hue, we spent three days in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, where much of our conversation revolved around issues of redevelopment and preservation in this cosmopolitan, rapidly expanding city. Ho Chi Minh City is a port city on the Saigon river with a population of roughly 9 million people. In the 17th and 18th centuries, waves of Chinese arrived by sea and established their own thriving economic center south of Saigon in Cholon. Unlike the establishment of the French Quarter in one section of Hanoi, when the French colonized Saigon in the 19th century they rebuilt the whole of the city in their image. Cholon, however, remained under the influence of the ethnic Chinese. On our third day in Ho Chi Minh City, Duk led our group on a walking tour of Cholon, known for its colorful Chinese-style temples and incredibly diverse shop houses — buildings with shops on the ground floor and living quarters above. I took hundreds of photographs of the shop houses, each one so different in design, color, and stylistic embellishments (Fig. 27). They made for a spectacular visual landscape!

The French also brought many Southern Indians with them to Saigon; they served as officials under the colonial regime, and their influence can still be felt in the many Hindu temples that dot the city. We visited the Sri Tenday Yuttapani Temple with its rooftop Vimana tower that attested to the amalgamation of cultures that exist in southern Vietnam (Fig. 28). Saigon was the base for the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, and the city continues to have a large foreign population. Today, international influence can be seen in the large amount of foreign investment and building going on in the city. Japan’s Shimizu and Maeda Corporations have teamed up to construct the first subway line in Ho Chi Minh City, and a Taiwanese company is responsible for the most successful planned community in all of Vietnam, Phu My Hung.

Fig. 27: A row of shop houses in Cholon

Fig. 28: The Vimana dedicated to Ganesh. Note the influence of western imagery in the clothing of the two male figures above the deities.

Fig. 29: A mishmash of architectural forms in Ho Chi Minh City. This photograph was taken from Gustave Eiffel’s Rainbow Bridge (1882), looking out at the State Bank (1924-8) and Carlos Zapata’s Bitexco Financial Tower (2010), which is meant to resemble a lotus.

Fig. 30: A detail of the curious decorative motifs on the façade of the Center for Urban Preservation Studies, a former colonial villa which housed the Ècole française d’Extrême-Orient.

Construction is going on everywhere. As a result, historic structures in Ho Chi Minh City are dwindling. Still, it makes for a fantastic built environment when you can observe a sleek, contemporary glass monolith, a string of modernist shop houses, and a former French colonial villa in one glance. At one point, we were standing on an iron bridge built by Gustave Eiffel’s firm in 1882, looking out at the former Bank of Indochina (1924-8) with Carlos Zapata’s 68-floor Bitexco Financial Tower (2010) rising in the background (Fig. 29) In the other direction, all we saw were cranes.

One of the primary victims of this rampant redevelopment is the colonial villa. The Center for Urban Preservation Studies, a cooperative project funded by the Vietnamese and French governments, is located in the former headquarters of the Ècole française d’Extrême-Orient (Fig. 30). On our first day, we visited the Center to learn about their investigation of the loss of colonial villas in Ho Chi Minh City and how they advise local authorities on preservation issues. An inventory of public buildings was conducted in 1998. The Center recently revisited this inventory and found that 55% of the buildings documented have since been demolished. The Center would like to provide realistic legal guidelines in order to harmonize development and heritage in a city that identifies as a fast-changing global metropolis. To do so, they have defined the heritage criteria of the colonial villa and developed a methodology for analyzing the buildings. The villas can be classified as exceptional, remarkable, or normal. The exceptional category earns them government protection; the remarkable category requires that features of the building be incorporated into new development; and the normal category receives no form of protection. About twenty buildings have already been classified in the central district of the city.

In Focus: French Colonial Style in Saigon

Despite the rapid rate of development in Ho Chi Minh City, French colonial-era neoclassical buildings still make up the bulk of the monumental structures in the city center. This includes government institutions, leisure facilities, military barracks, schools, hotels, and markets. Throughout our three days in Ho Chi Minh City, we visited the Central Post Office (1891), Notre Dame Cathedral (1880), the façade of the former opium refinery, the Opera House (1900), multiple early twentieth-century hotels that line the historic Dong Khoi Street, the former City Hall (1909), the former Customs House (1863), the Saigon State Bank (1928), Ben Thanh Market, the Museum of Vietnamese History and the Hùng King Temple at the Zoo and Botanical Gardens (1929), the former military barracks (1870-73), the Convent of Saint-Paul de Chartres and St. Joseph’s Seminary, the Khai Minh Primary School (1920s), and the Ho Chi Minh City Fine Arts Museum (1929-34). Phew!

Of these, we spent the most time exploring the Central Post Office and the buildings at the Zoo and Botanical Gardens, and for good reason. Completed in 1891, the Central Post Office was designed by Alfred Foulhoux, the Head of Public Works for the French government in Vietnam. It is a typical 19th-century Baroque building with clear connections to the building programs of the turn-of-the-century international expos, particularly in the heavy use of iron. The iron marks the industrial function of the building, and it is put to decorative use in the impressive arched interior (Fig. 31). The giant clock on the façade and the maps that decorate the interior walls reiterate the primary function of the post office—the theme of modern communication. At the time of its construction, it would have taken about thirty days for mail to travel from France to the colony.

Fig. 31: The articulated arched interior of the Central Post Office, designed by Alfred Foulhoux

Fig. 32: Exterior view of the Museum of Vietnamese History, designed by Auguste Delaval in a hybrid Vietnamese-French style.

Fig. 33: The interior courtyard of the Museum of Vietnamese History

The Zoo and Botanical Garden was one of the first spaces mapped out by the French, as it would become an important part of the international network of scientific exchange used to develop crops and plants that could be economically lucrative for the colonial government. It is still one of the largest green spaces in Ho Chi Minh City, where there is only 0.7 square meters of green space per person! Understandably, the public values the space and continues to maintain it despite its colonial origins. The Museum of Vietnamese History and the Hùng King Temple (formerly the Temple du Souvenir Annamite) were built as part of the massive expansion of the zoo and gardens in 1929. The museum was meant to display the artifacts collected by the Society of Indochina Studies, and the temple was built as a memorial to the Vietnamese soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. Both were built in a hybrid Vietnamese-European style that reminded us of Ernest Hébrard’s museum for the Ècole française d’Extrême-Orient in Hanoi (Fig. 32). I find it curious that architects are consistently drawn to the roofing elements of Asian architecture when attempting to create an integrated style. More than the roof, I thought that the museum was successful in its incorporation of an interior courtyard, which helped with ventilation in the exhibition halls while also paying tribute to the important space of the garden in Asian vernacular architecture (Fig. 33).

In Focus: Modernism in Saigon

On our second day in Saigon, we arrived at the Ho Chi Minh Museum for a short lecture by Mel Schenk on the state of contemporary architecture in Vietnam. The museum itself was an interesting structure that sparked some controversy in the group! It is nicknamed the “Dragon House” for the dragon sculpture that adorns the rooftop, and the general plan was inspired by the vernacular “huts” that the French discovered when they first arrived in southern Vietnam (Fig. 34). It also has the feel of a military structure with the linearity of the plan echoing the uniform patterning of barracks. We were told that it was built in 1863 as the Customs House for the French colony, but our architecture whiz Miles was quick to point out that the building was constructed in reinforced concrete. He suggested that we re-date it to the 1920s, and just like that we had rewritten a part of Ho Chi Minh City’s architectural history! This anecdote is actually quite telling of the current state of historical work being done in Vietnam and of what is required for conducting research there. There is very little in the way of archival records, and thus much of the research necessitates direct contact with the buildings and close visual observation.

It is for this reason that we were all thrilled to hear from Mel Schenk, who has been roaming and documenting the built landscape of Ho Chi Minh City in order to put forward some theories about the heritage of modernism in Vietnam. Schenk is an American architect living in Vietnam. He taught us about the communist revolutionary leader Huynh Tan Phat, who established the first architecture firm in Saigon in 1940 after graduating from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1938. He designed many modernist villas, as well as the podium from which Ho Chi Minh read the Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945. After 1945, Phat entered politics, serving as the Prime Minister of the Viet Cong in the Provisional Revolutionary Government until the country was formally unified in 1976. Schenk pointed out that having an architect in such an influential position was highly advantageous for the acceptance and spread of modernism by the government.

Fig. 34: The Ho Chi Minh Museum and former Customs House in Saigon.

Fig. 35: The modernist Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City

Fig. 36: The design of the Rex Hotel was inspired by the layout of a cruise liner.

Fig. 37: The bold modernist monument, Turtle Lake

Schenk believes that overt modernist architecture has flourished in Vietnam unlike anywhere else in the world. Walking and busing around Ho Chi Minh City for three days, it was not difficult to understand why. The years 1940 to 1975 are considered the heyday of modernism in Vietnam, and we visited many of the masterpieces that remain from this period. Of them, the Reunification Palace stands out for its large footprint as a visual anchor in the city (Fig. 35). The Palace was bombed in 1962, after which a design competition was held for its rebuilding. Many of the proposals were classical in style, but the 1955 Rome Prize winner Ngo Viet Thu was selected as the architect for his modernist grid-like proposal. The Rex Hotel from 1957 appears like a direct interpretation of Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture—a building inspired by a cruise liner with its receding tiered levels and round porthole windows (Fig. 36) The University of Architecture, designed by a graduate of the school in 1972, and the Ho Chi Minh City Eye Hospital both make references to Bauhaus architecture. Turtle Lake (1975), one of the few monuments to survive from the 1970s, is an abstracted, geometric sculpture built according to the Taoist belief that the dragon of southern Vietnam was located in the area. A feng shui master advised the designer that the tail of the dragon needed to be controlled in order to bring stability to the region, and, thus, the monumental sculpture resembles a sword that has been plunged into the ground to pin down the tail of the dragon (Fig. 37).

In addition to these masterpieces, the shop houses (yes—those again!) reiterate Schenk’s point about the proliferation of modernism in Ho Chi Minh City. In his words, “The modernist shophouse is the vernacular architecture of Vietnam.” I’ve already elaborated on the amazing diversity of these designs, but it is worth pointing out that such diversity attests to the wide-ranging experimentation that has occurred in Vietnamese modernism. These houses take up 100% of their lots, and so the facades become opportunities for experimentation in composition, color, shapes and textures. Some of the most successful experiments consider the climate of Vietnam and can be seen in innovative sunshades, trellises, and screens (Fig. 38).

Fig. 38: More innovative shop houses from the Cholon district of Ho Chi Minh City

Fig. 39: Vo Trong Nghia’s Wind and Water Café, made with locally treated bamboo and minimal steel

According to Schenk, contemporary architecture in Vietnam is increasingly concerned with issues of sustainability while being firmly based in this history of modernism. Today, increasing attention is paid to materials; to creating open, airy spaces; and to the inclusion of green spaces. In this field, the architect Vo Trong Nghia stands out. He was born in 1976 and attended the University of Architecture in Hanoi after which he received his PhD from the University of Tokyo. His buildings can be categorized into two main types of projects: green spaces and bamboo spaces. The greenery projects include houses such as the Stacking Green in Ho Chi Minh City, which has a façade made entirely of concrete plant holders of varying shapes and sizes. The plants function as a natural filter for the bright sunlight in southern Vietnam and purify the air of the house. It represents Vo Trong Nghia’s attempt to “bring the forest back” to the city of Saigon. We were lucky to be able to drive out to see one of Vo Trong Nghia’s other projects, the Wind and Water Café, which was completed in 2006 near a resort complex in the suburbs of Ho Chi Minh City. The open-air café consists of one oblong steel and bamboo butterfly roof wrapped around a central water feature and supported by sprouting bamboo columns (Fig. 39). The bamboo is treated locally—soaked in mud and smoked—in this cost-efficient, durable, and ecologically-minded design. Vo Trong Nghia calls bamboo the “steel of the 21st century,” and predicts that the columns and roof support will need to be replaced every twenty years. We were able to sit under the structure for a while to enjoy the wonderful wind flow that acts as a kind of natural air-conditioning for the café. I think I also enjoyed the best coffee of my life there—it was like drinking liquid chocolate!

Day 8: Siem Reap, Cambodia

Before we knew it, it was time to leave Vietnam for Cambodia. For many of us, visiting the ancient temples in Siem Reap was a big motivation for joining the tour. And yet, these complexes still managed to defy all expectations. No photograph of Angkor Wat can truly capture what it is like to approach the structure on the long causeway leading up to the first gate, to walk along the amazingly well-preserved bas-reliefs that line its walls, or to climb up to the central sanctuary of this “mountain temple.” I felt like I could have spent weeks just at this one site attempting to explore all of its nooks and crannies, taking in all of the spectacular sight lines, and processing the intricate details of the stories told by the carvings. It is the kind of place that makes you want to quit your job and move there to become a tour guide, just to be in its presence all the time and to learn everything that there is to know about its history (Shh! Don’t tell my advisor!).

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Angkor Wat is the largest religious structure in the world (Fig. 40 / Caption: A general view of the five lotus-shaped towers of Angkor Wat). It was built from 1113-1150, faces west, and is dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. It is classified as a mountain temple, an architectural model that comes from India but flourished in the Khmer empire in revolutionary ways. The layout consists of a surrounding moat and a wall enclosing five lotus-shaped towers — one at the center to represent Mount Meru where the Hindu deities reside and four other “mountains” at the corners. Some of the stones were quarried as far as forty-five miles away and transported to the site by bamboo boats and elephants. No nails were used in the construction — just layers and layers of laterite, brick, sandstone and stucco.

Fig. 41: Corbelled vaulting in one of the passageways at Angkor Wat

Fig. 42: A detail of the bas-relief depicting the Churning of the Sea of Milk

Corbelled vaulting was employed to achieve the immense height of the towers, but this system of construction also makes for rather narrow spaces (Fig. 41). Because of this, there is no large covered space within the complex for the gathering of pilgrims or worshipers. Instead, Angkor Wat is characterized by its layers of passageways and enclosures, all decorated with carved reliefs and passages in Sanskrit. Professor Hahn encouraged us to note the relationship between perspective and movement; every time you move outside and within the complex it seems to change dynamically.

Some of the reliefs, such as the Churning of the Sea of Milk or the depictions of Heaven and Hell, are in remarkably good condition (Fig. 42). The French began restoration and preservation efforts when they established a protectorate in Cambodia in 1863, but many countries and international organizations contribute to the necessary maintenance, restoration, and archaeological work that continues today. It is incredibly prestigious to head the preservation of one of the ancient temples in Angkor. In my own research, I am interested in how countries without comparable sites appropriate these temples as “Asia’s ruins” through preservation work and financial support. When thinking about a country’s involvement with UNESCO, it is important to consider not only applications for UNESCO status within that country’s borders, but also their involvement in neighboring regions.

Day 9: Siem Reap, Cambodia

King Jayayarman VII was the last major king of the Khmer Empire. He ruled from 1181-1220 and constructed more religious monuments and public facilities than all of the other kings combined. On our second day in Angkor, we visited many of the sites built by “J7,” the nickname given to Jayayarman VII by our local tour guide so as to accommodate our foreign ears.

The first stop of the morning was Angkor Thom (1181-1218), a 2x2 square mile enclosure built by J7 to protect the capital and its 70,000 inhabitants after the Champa invaded Angkor in 1177. The relief carvings on the entrance gate and surrounding wall reinterpret the adventures of Indra as the battle between the Champa and the Khmer (Fig. 43). While most of the temples in Angkor are dedicated to Hindu gods, J7 adopted Mahayana Buddhism as the state religion in addition to Hinduism. Thus, the towers with carvings of giant faces on each side that are unique to Angkor Thom could be interpreted as the face of Buddha, the face of Brahma, or the face of the deva raja, King Jayavarman VII himself reincarnated as a god. Inside Angkor Thom, Bayon Temple (1181-1220) boasts fifty-four of these four-faced towers arranged throughout a series of concentric enclosures with a circular sanctuary at the center. Walking through the complex you are constantly surrounded by these giant benevolent faces looking out in all four directions (Fig. 44). They are a truly unusual and remarkable development of the mountain temple style in Angkor. In Angkor Thom, we also visited the Terrace of the Elephants and the Terrace of the Leper King. While the function of the latter is unknown, the Terrace of the Elephants was used as a stage for royal ceremonies in front of the Freedom Courtyard. At 350 meters long, it gave us a sense of the magnitude and grandeur of J7’s reign.

J7 built two monasteries, one for his mother and one for his father. Ta Prohm was built in the late-12th/early-13th century for his mother. This is where the Angelina Jolie blockbuster Tomb Raider was filmed. It is incredibly atmospheric due to the 500-year-old sponge trees that have taken over the buildings (Fig. 45). When the French first “rediscovered” Ta Prohm, they decided to leave the trees as they were, integrated throughout the walls of the monastic complex. They did this for a variety of reasons: 1) to maintain the romantic, exotic atmosphere of the site; 2) to legitimize claims that the temples were in ruins and in need of repair by the French; and 3) for the very practical reason that some of the structures would simply fall apart without the roots and vines of the trees holding them together. Thus, Ta Prohm gives you an idea of what many of the sites might have looked like when the French first arrived in the nineteenth century. But don't be fooled: a lot of work goes in to keeping this site in ruins! The trees are checked every six months and stray branches are removed to maintain the stability of the ruinous structures.

Fig. 43: A bas-relief depicting the battle between the Khmer and the Champa

Fig. 44: One of the towers of Bayon Temple with the face of Buddha, Brahma, or the deva raja.

Fig. 45: A sponge tree among the ruins of Ta Prohm, the monastery that King Jayavarman VII built for his mother.

Fig. 46: Ruins at Preah Khan that resemble Greco-Roman temples.

Preah Khan, or the “Sacred Sword,” was built by J7 in 1191 for his father. It is another monastery where many of the structures are still in ruins, and parts of it are said to resemble Greco-Roman temples (Fig. 46). The complex is huge — 630,000 square meters with an enclosure wall carved with seventy-two five-meter-tall garudas. Here, again, Hinduism and Buddhism have been incorporated together in the relief carvings. There is also evidence of the widespread iconoclasm that occurred after J7’s reign, in which many of the Buddhist images were erased or re-carved to resemble Hindu iconography.

There is a popular phrase for sightseeing exhaustion in Angkor; it’s called being “templed out.” Many succumb to this unfortunate condition, but not us! The other sites that we visited that can be attributed to J7 were the Srah Srang, or the king’s bathing pool (more like a small lake), which J7 modified in 1200; and Neak Pean, or the “Coiled Serpent,” an artificial pool with a sculptural interpretation of nirvana at the center where pilgrims would received blessings. On our second day we also visited many temples and structures that were not built by J7, including the five brick towers of Prasat Kravan (921); the so-called “changing body” temple, Pre Rup (961); and a similar mountain temple, East Mebon (952). Of the non-J7 sites, I was the most deeply impressed by the temple Ta Keo (1000-1025). Ta Keo is a mystery among the temples in Angkor because it is unfinished, and its unfinished nature is precisely why it was worth a visit. Because it is lacking decoration, we were able to examine the ways in which the temples were put together before they were carved into the rounded shapes of mountains or the faces of deities (Fig. 47). There is absolutely no mortar between the stones—simply sand that was ground down into a resin to help keep the blocks in place. At Ta Keo, you can more easily identify the different stones that were used in the layering of colors that make up the walls and towers.

Fig. 47: Looking up to the undecorated towers of Ta Keo

Day 10: Siem Reap, Cambodia

On our final of the tour we had an early morning departure for two sites about 25 kilometers northeast of Angkor Wat. The first stop was to Banteay Srei, a temple that was rediscovered during a French geographic survey in 1914 and reconstructed using anastylosis from 1931-36. Miles gave our group a lesson on the ethics of anastylosis, which literally means, “raising the columns” in Greek. As opposed to earlier techniques in which monuments were restored according to how the French thought they might have appeared, with the method of anastylosis, preservationists attempt to restore the monument as authentically as possible without adding anything that wasn't there at the site to begin with. They take what is on the ground and put it back in its correct place like a puzzle; hence, “raising the columns.”

Banteay Srei (967) was built by two different kings in laterite, brick, and a noticeable pink sandstone. It is well known for the exquisite state of its relief carvings, which are the oldest and arguably the most impressive in the area (Fig. 48). One lintel features a carving of an incarnation of Vishnu with an animal head and human body tearing open the chest of a demon. Bordering this scene is an eye-catching flowing sequence of a dragon swallowing an elephant which morphs into a lion and then melds into carvings of flowers. You could get sucked into this site for hours exploring all of the details of these reliefs. It’s almost difficult to comprehend that much of what you see is the original artwork in situ — that it hasn't been carted off to be preserved in a museum. The opportunity to observe all of the original work in relation to the entire site is a gift that is increasingly rare at historic sites.

Fig. 48: Bas-reliefs on one of the towers in the central sanctuary of Banteay Srei

Fig. 49: Shiva carved into the riverbed at the “River of a Thousand Lingas.”

Fig. 50: A scene from our final hike through the jungle near Phnom Kulen

Our final stop was another unforgettable opportunity to examine carvings in their original setting. Kabal Spean means “Head of the Bridge,” but this site is also referred to as the “River of a Thousand Lingas.” After about forty-five minutes of hiking through the jungle, we arrived at a river to find Hindu imagery carved directly into the riverbed. The carvings were done in the 11th century by ascetics who spent time at Phnom Kulen, the most sacred mountain in all of Cambodia where the Khmer monarchy was founded. As we walked along the river, we encountered carvings of Shiva, lotus blossoms, and a natural sandstone bridge with 1,000 lingas sculpted on the side (Fig. 49). The entire journey felt otherworldly. You could easily understand why these holy people of the 11th century chose the site as a retreat from the city in Angkor. The hike through the jungle — as strenuous as it was! — made for an ideal ending to this whirlwind of a trip (Fig. 50). I was able to meditate on the incredible range of structures and spaces that we had experienced during our time in Southeast Asia, from the teeming, energetic streets of the Old Quarter in Hanoi to the moss-covered ruins of royal mausoleums in Hue, or the spectacular view of Ho Chi Minh City from the top of Carlos Zapata’s Bitexco Financial Tower and the endless layers of stone, brick and trees in the temples of Angkor. I am endlessly grateful to the Society of Architectural Historians for this humbling opportunity; to First Vice President of SAH Sandy Isenstadt for his steadfast leadership and good humor; to our kind, knowledgeable and tireless guide, Professor Hazel Hahn; to the travel extraordinaire, Sinéad Walshe from ISDI; and to all of my new friends and mentors who taught me a great deal about the virtue of travel for the sake of knowledge. Cảm ơn! Arkoun! Thank you!

Carrie L. Cushman is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University. She specializes in Modern Japanese Art and Architecture, with research interests in modern ruins, the aesthetics of disaster, urban redevelopment, and the role of ruins, both natural and man-made, in narratives of history. Her dissertation focuses on the photographer Miyamoto Ryūji, whose images of ruins engage multiple layers of trauma in the contemporary Japanese experience. Carrie was the recipient of the 2014-15 Meyerson Teaching Award in Art Humanities at Columbia. In 2015-16 she conducted research for her dissertation as a Fulbright Graduate Research Fellow in Japan, where she continues to work and write.