With the generous support of a Scott Opler Endowment for New Scholars Fellowship, I was able to attend SAH’s “Louis Kahn Study Day” on Friday, November 4. My aim was to think through some of the questions that I am currently exploring in my own work about how, as a living monument, Kahn’s National Assembly Building in Dhaka participates in contemporary political debates about representative democracy in Bangladesh. In early 2014, the Government of Bangladesh announced plans to erect a fence/barricade around the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, one of Kahn’s most iconic monuments. In response, a group of Bangladeshi performance artists staged protest performances, using the iconic face of the building as backdrop. But can architecture ever serve as a mere backdrop? Indeed, how might architecture’s entwining of place, extension in space, and time speak to similar concerns within performance art? With these questions in mind, I set out to explore how Kahn’s oeuvre was being brought to life at the San Diego Museum of Art’s exhibition and through conservation efforts at the Salk Institute.

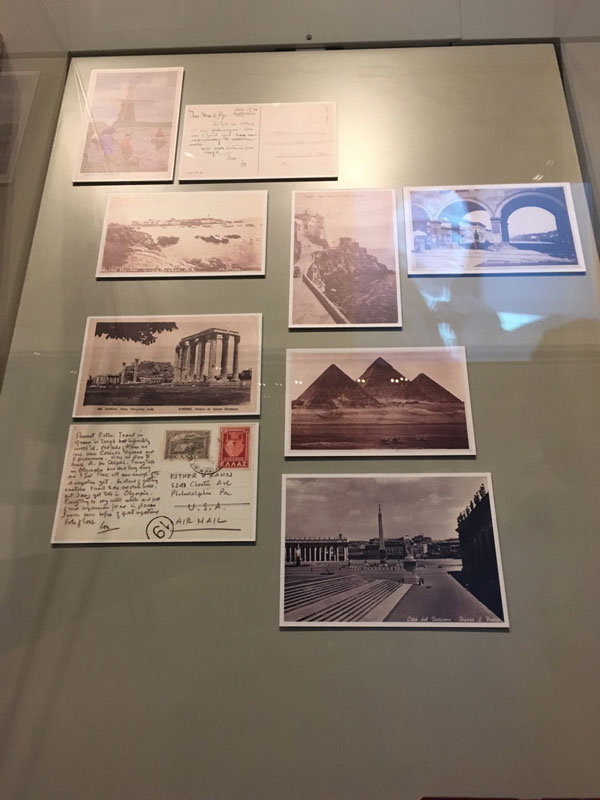

Installation of Louis Kahn's travel postcards at SDMA exhibition Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture.

The exhibition Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture at SDMA comprises six sections in addition to an introduction: “Science,” “City,” “Landscape,” “House,” “Community,” “Eternal Present.” These sections not only highlight Kahn’s fluid movement across domains of public and private architecture, as well as urban planning, but they also illuminate how Kahn’s exploration of space (especially as scale and as extension in time) unfolded both in his creative practice as well as his lived reality. For example, the exhibition’s curators, William Whitaker and Jochen Eisenbrand, invited us to think about how the automobile informed Kahn’s thinking about the hierarchy of streets (fast lanes vs. slow lanes; pedestrian zones) in his urban planning projects. This observation stayed with me as I moved along an exhibition that invited me to retrace the journeys that Kahn undertook, by ship and by jet plane, across the world, from his pursuit to study ancient architecture to his travels in South Asia. It then made me think about the views that unfold as one walks along the ambulatory chambers of the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, and that both underscore the impressive scale of the building and yet localize that scale to an ecstatic burst of instants that nonetheless always spill over into an adjacent space.

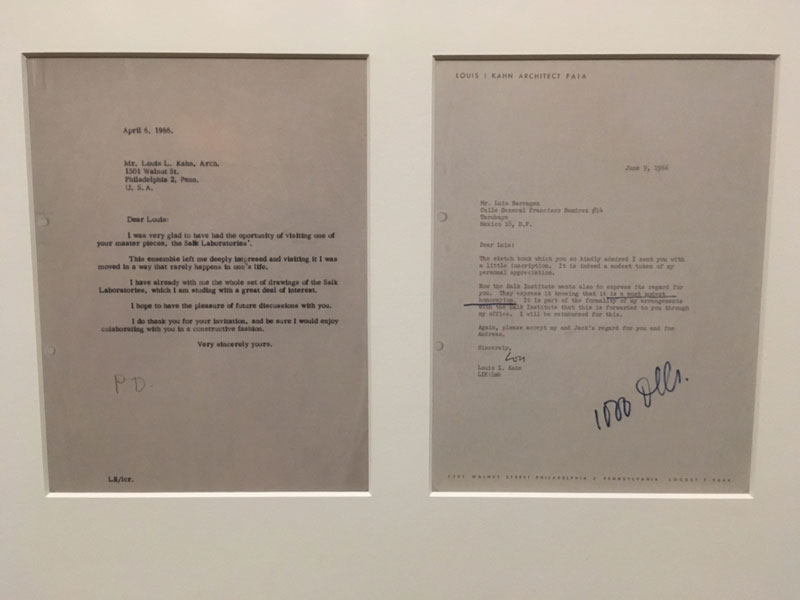

One of my favourite objects from the exhibition was Luis Barragan’s sketch for the plaza of the Salk Institute. As the curators informed us, and as the exhibition narrates through four letters exchanged between the two architects, Kahn admired Barragan’s work as a landscape architect and invited him to help him come up with a design for the area between the North and South towers. Barragan reported to Kahn after his visit that a plaza was the best choice for it. Kahn’s gesture to reach out to another fellow architect, in this case Barragan, was not rare in his practice. Seeing then four letters between “Louis” and “Luis” and reflecting on how Louis Kahn, thanks to a typographical error, is acclaimed as “Luis Kahn” in my Bangladeshi passport, I wondered how we could move away from authorship and situate Khan’s work in the productive echoing and accenting of Louis/Luis. Is this one of the many points from which we can write a global history of architecture?

Luis Barragan, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Study for Design of Interior Courtyard, 1966.

Letters exchanged between Luis Barragan and Louis Kahn.

Plaza (designed in consultation with landscape architect Luis Barragan) shown with scaffolding. Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Louis Kahn, 1959, La Jolla, CA.

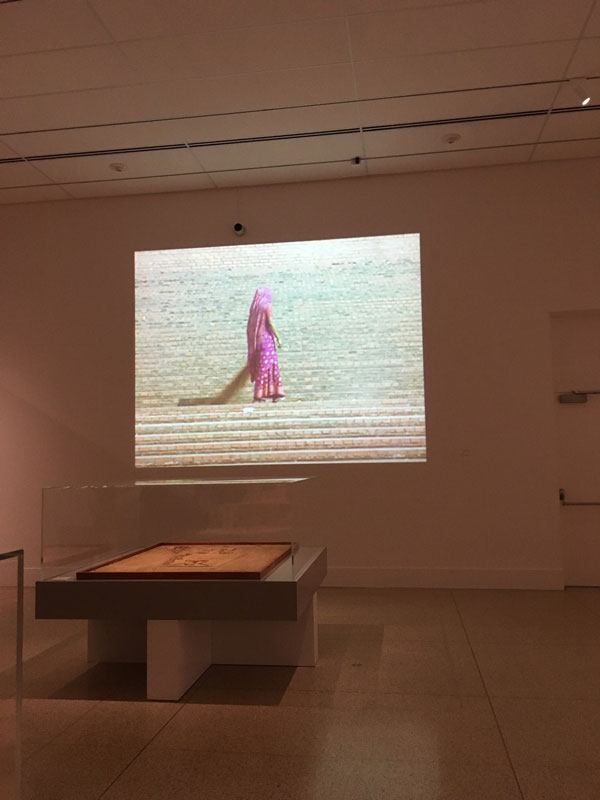

The installation of the designs, models, and construction photographs of the National Assembly Building are juxtaposed in the exhibition with a short film by Nathanial Kahn, created from footage that he took during the making of My Architect. Indeed, three short films by Nathanial Kahn help to highlight the multi-sensory environment in which Kahn’s buildings exist and which they engender. Thus, as one examines the large model of the National Assembly Building in the center of the room, one’s attention is enhanced/distracted by the sounds of rickshaw bells and then, upon looking up, by a view of a crowded Dhaka street. Next, the model is framed by a shot of a woman slowly sweeping the steps of the building. While the installation thus offered a juxtaposition of living monument (through the mediation of film) and model, it also made me wonder about the claim upon “contemporaneity” that was being made through it. In 2016, when few people in Bangladesh can gain close access to the Parliament building (its maidan is no longer open to the public), perhaps this nostalgic juxtaposition of model (as promise) and film (as relic) serve as reminders of the monument’s founding promise. Furthermore, by playing the sounds of the azaan, the film and the exhibition seemed to foreground the ambitions of the modern, post-colonial, Muslim nation (Pakistan) that commissioned Kahn’s project. In what way does Kahn’s monument engage with the vexed claims of secularity that inform political discourse in Bangladesh today?

National Assembly Building Dhaka. Short film made by Nathanial Kahn for the SDMA exhibition Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture from footage taken during the making of My Architect.

This promise of the return to the monument’s origins (in this case, Kahn’s vision for it) is echoed in the teak conservation project currently underway at the Salk Institute. There we learned about the precarious materiality of teak in the Southern California environment and how conservators have drawn upon Kahn’s archives in formulating a conservation plan. And we also learned about the urgency of teak conservation given regulations today about its importation. Standing in front of one of the newly-conserved teak windows, and reflecting on the use of teak in Kahn’s Dhaka project, I began to think about the global networks of Kahn’s projects that we encountered at SDMA. Thus, in addition to its conservation, how do we also situate teak in the post-colonial and global networks that delivered it from Southeast Asia to Southern California?

Teak windows at one of the North Study Towers. Salk Institute of Biological Studies, Louis Kahn. 1959, La Jolla, CA.

View showing horizontal and vertical details of the concrete. Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Louis Kahn, 1959, La Jolla, CA.

Zirwat Chowdhury is an NEH Postdoctoral Fellow at the Getty Research Institute. Her research concerns the interconnected histories of art and architecture in Britain and South Asia in the 18th and 19th centuries, but she has been interested in Kahn's National Assembly Building since she was a child.