The Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition, Latin America in Construction: 1955–1980, marks the first time since 1955 that the institution has examined architecture in Latin America. Participants in SAH’s MoMA/UN Study Day on March 27, 2015, were treated to a preview of the show by Dr. Barry Bergdoll, then-Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at MoMA and currently a professor of architectural history at Columbia University. Dr. Bergdoll opened the day by discussing the meaning of the exhibition title—construction as a metaphor for the making of architecture, construction of Latin American identity in the 20th century from both within the region and from the outside, and the (re)construction of a dialog between architects, countries, and ideas as Latin American architectural historiography undergoes reexamination. The goal of the show, he said, was to recalibrate the notion of “Latin America” as an architectural adjective toward a more nuanced understanding of both the parallels and differences in the built environment of all countries in the region.

Figure 1. Study Day participants exploring issues of housing in Latin America.

This theme, which runs through the entire show, was apparent upon entering the first room of the exhibition space. A series of hovering video screens displaying vibrant modern life in Latin America worked in tandem with architectural artifacts in order to convey a region in motion during the first part of the 20th century. Dr. Bergdoll explained that the works highlighted in this part of the exhibit were meant to contextualize pre-1955 Latin America as a region undergoing major development, growth, progress, and modernization—a region well on its way in its own way—rather than an empty receptacle waiting to receive architectural instructions from the United States or Europe.

The second exhibition space contained drawings, models, photographs, and sketches for the Ciudad Universitaria in Caracas, Venezuela and the Ciudad Universitaria, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City. Participants had the chance to examine various site plans for both projects. The spectacularly detailed watercolor façade study of Juan O’Gorman’s Biblioteca Central on the UNAM campus was one highlight in this section. Dr. Bergdoll explained that architects in Latin America tended to take a more urban approach to university campuses, using them as tools for regionally contextualized urban development. The UNAM, according to the exhibit, coupled the functional city planning of CIAM with the spatial planning of Teotihuancan, allowing for a carefully planned urban environment with an expanded ceremonial center influenced by pre-Columbian cities. Additionally, the university plan took the natural environment and contours of the land into consideration. A beautifully rendered site plan by Mario Pani and Enrique del Moral Dominguez detailed how campus classrooms, living quarters, and landscaping were situated in harmony with the ancient lava flows upon which the UNAM was built.

Figure 2. Drawings and artifacts for the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City. Juan O’Gorman’s 1952 watercolor façade study of the Biblioteca Central is on the far right, and the ink and watercolor site plan by Mario Pani and Enrique del Moral Dominguez is second from the right.

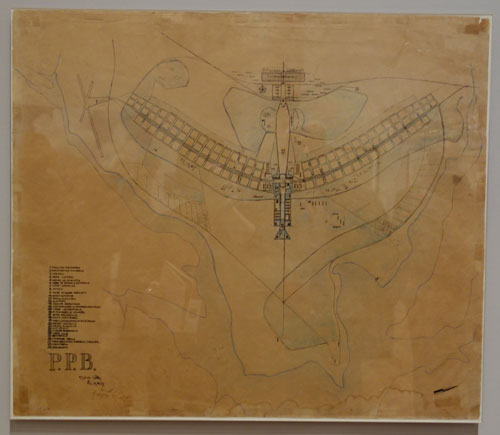

As the group progressed to the next space, the link between campus and city in Latin America became clear. In his introduction, Dr. Bergdoll had described campuses in Latin America as urban laboratories and wondered if those campuses should be considered small urban areas or if bigger developments like Brasilia should be considered large campuses. With this in mind the group entered the world of Brasilia, learning that it was intended to represent 50 years of development in 5 years (because of presidential politics, of course!), with an astonishing completion time of only 41 months. Lucio Costa’s schematic plan conveyed the progressive spirit of the capital city, described by Dr. Bergdoll as a ceremonial center and highway version of a garden city. Pointing to Costa’s plan for Brasilia, Dr. Bergdoll then shared a story about the moment he was first handed the drawing—the sheer exuberance of holding in his hands the “birth certificate” of the city.

Figure 3. The winning competition entry for the Pilot Plan of Brasilia, by Lucio Costa in 1957.

It was evident from the beginning of the show that each part of the exhibition space was carefully considered. The galleries were arranged to visually reinforce the notion that Latin America’s architectural development intertwined both regionally and globally—walls opened up and long views were created as the spatial progression of the exhibition unfolded. These critical perspectives revealed commonalities between cities, architects, and architectural form language, as well as revealed differences.

Figure 4. Participants exploring in the open, intermingled spaces of the exhibition.

The use of architecture to create public grounds and the interrelationship between interior and exterior experience emerged as two such commonalities. The placement of Lina Bo Bardi’s Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo (MASP) model within the exhibition underscored the notion of architecture as a tool for the reorganization of community and public space, with its emphasis on creating simultaneous views of the city and of the landscape beyond.

Figure 5. 1957 model of Lina Bo Bardi’s Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo (MASP) in Brazil.

The second part of this whirlwind Study Day took participants to the newly restored UN Headquarters Building, a fitting complement to the morning’s topics of discussion. The group was met by Assistant Secretary General Michael Adlerstein, executive director of the UN Capital Master Plan. Mr. Adlerstein was responsible for overseeing the complex’s recent $2 billion restoration. He described the meticulously restored public entrance of the General Assembly Building—pointing out the first-of-its-kind exposed ceiling ductwork, the functionally and structurally integrated heating and cooling system, and the lyrically curved forms of the balconies above. He then led the group into the iconic UN General Assembly Hall. The scope and magnitude of the entire restoration project was made clear through the experience of this one room. Every element of the vast space, according to Mr. Adlerstein, was painstakingly removed, restored, and reassembled. Original colors and materials were also either restored or maintained. Returning the gold luster to the long vertical slats encircling the podium seemed to be a particularly challenging project, requiring the removal of tar and cigarette stains accumulated over the decades. The slats were not composed of darkly stained wood after all, as one participant had originally assumed!

Figure 6. The recently restored UN General Assembly Hall by Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Wallace Harrison, and an international team of architects.

The group then wound its way through various meeting spaces in the Secretariat Building, past vast planes of green-tinged blast glass and displays of art and artifacts donated by participant countries. The group was also able to observe a UN Millennium Development Project meeting in progress. Finally, the day concluded with a rooftop reception at the home of participant Konrad Wos, which overlooked the entire UN complex.

I am incredibly grateful to the SAH for the opportunity to attend the MoMA/UN Study Day as the Scott Opler Endowment for New Scholars Study Tour Fellow. I would also like to thank Barry Bergdoll, Michael Adlerstein, Konrad Wos, and SAH representative and host Sandy Isenstadt for taking the time and effort to provide the participants of this Study Day with an unforgettable experience.

Jennifer Tate, PhD Candidate, University of Texas

Jennifer Tate, PhD Candidate, University of Texas Jennifer Tate is a PhD candidate in architectural history at the University of Texas in Austin. Jennifer holds a master's degree in architectural history from the University of Texas in Austin, as well as graduate degrees in political science from Georgetown University and international policy studies from Stanford University. She received her BA with honors in political science and mathematics from Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Jennifer is interested in the intersection of politics and power relations with architecture, especially in the examination of center-periphery issues and the related international-regional divide in modern architecture. She has a secondary interest in modern Turkish architecture.