We had already seen one of the three “Proyectos Grandes” of the early years of the Revolution when we saw Habana del Este. Today we were going to see the other two: CUJAE (Ciudad Universitária José Antonio Echeverria (1959-1965) and the Escuelas Nacionales de Arte (1959-1964). That the three “Proyectos Grandes” were a social housing project and two universities reinforces the Revolutionary governments emphasis on housing and education. We first visited CUJAE, where Dr. Jorge Peña Diaz, professor in the architecture department, gave an introductory presentation on the architecture of the university and the current work of the university. Looking at the architecture it was apparent how the architects embraced the creative possibilities of using modular building systems. The campus really is like a city, with covered walkways (to protect against rain) connecting buildings and creating sheltered areas for students to gather and interact.

Before lunch we made a quick stop at the

Reparto Abel Santamaria, an area of a neighborhood composed of circular houses and a circular market. We had the opportunity to enter the market building, where Osmin explained to us how Cubans by food with their ration cards.

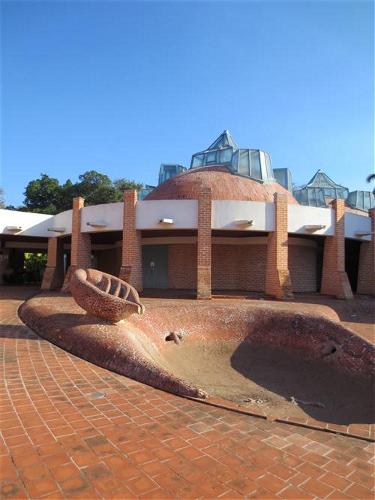

For many of us, we had been looking forward to our visit to the Escuelas Nacionales de Arte (Nacional Schools of Art) before the trip started and the lived experience did not disappoint. The visit was all the more memorable thanks to Universo Garcia, the architect in charge of restoring the schools who accompanied us throughout the campus. This campus was quite a contrast to CUJAE. While the architecture of CUJAE is cohesive and based on a modular system, at the National Schools of Art the different schools are spread out across the land and rendered in highly individual and expressive styles often reliant on traditional building techniques. We first visited the School of Plastic Arts, designed by Ricardo Porro, who also designed the School of Modern Dance and was the lead designer of the project. Universo described how Porro’s design for the School of Plastic Arts was an homage to Cuban roots, and he looked to African villages and the Santería goddess of fertility. The school has been beautifully restored, and Universo described the various interventions made in the restoration and his hope for future maintenance.

We then moved on the School of Music, designed by Vittorio Garratti, an Italian architect that Porro had befriended while at Carlos Villanuevas’s office in Caracas, Venezuela. A visit to the School of Music allowed us to see how much had been done with the restoration of the School of Plastic Arts. The beautiful Catalan roof vaults there were a sharp contrast to the School of Music, where we saw the roofs crumbling because of the tile delamination.

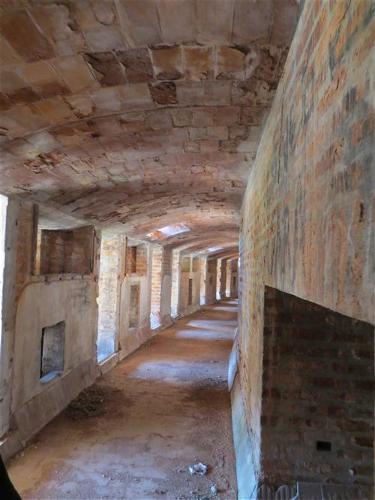

We then visited Garratti’s other contribution, the School of Ballet, which was near completion when Alicia Alonso, head of the National Ballet, declared that the school was unfit and the company would not move there. Visiting this school was an adventure, as we had to cross a half-collapsed bridge to get to the school. This school was the most haunting to me, with large cavernous openings for practice areas, and curving hallways punctuated by openings in the ceiling that let in disorienting strips of light.

Our final visit was to the School of Modern Dance, also designed by Porro (we were unable to visit the fifth school, the School of Dramatic Arts). This school also reminded me of an African village, though I’m not sure if this was Porro’s intention. Like the School of Plastic Arts, this school is still being used, and we could here music coming from some of the classrooms, and students were presumably training inside.

Erica N. Morawski, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Illinois - Chicago

Erica N. Morawski, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Illinois - Chicago

Erica N. Morawski is a Ph.D. candidate in art History at the University of Illinois – Chicago. She received a BA in art history at Tulane University and MA in Art History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently completing a dissertation entitled, “Designing Destinations: Hotel Architecture, Urbanism, and American Tourism in Puerto Rico and Cuba.” This work investigates the role of hotels in shaping understandings of national identity, which in turn shaped international relationships, through an approach that systematically ties object and image analysis with social, political, and economic histories. Her work argues that these hotels functioned, and continue to function, like diplomatic cultural attachés—their design shaped politics on the islands, and played a decisive role in shaping past and current international relations.