by Amber Wiley

Kahn’s career in residential work began with the Jersey Homesteads project (1935-36). This was a collaborative effort with Alfred Kastner, who served as principal architect of the project. Kastner, a German immigrant, was strongly influenced by the Bauhaus aesthetic. Various forces shaped the development of the neighborhood which was an initiative of Roosevelt’s New Deal era, created under the New Deal Resettlement Administration. The visionary for the development was Benjamin Brown, and the main developer was Rexford Guy Tugwell. The Jersey Homesteads project is regarded as part of the greenbelt movement, an idyllic suburban movement that had at its basis a rejection of the city for the bucolic effects of the country, with strong moral undertones.

Jersey Homesteads was considered a “social experiment in cooperative living,” where families who previously resided in unfavorable conditions in tenement filled New York were relocated to rural New Jersey with the promise of a better life, a better house, and the security of a job. Part of the development’s main appeal was the creation and inclusion of a garment factory and farm, and the families paid $500 for their share in the co-op.

The Jersey Homesteads became a miniature haven for various artists during the New Deal era. Muralist Ben Shahn was one of the first and most prominent artists to move into the development. We toured the house where he lived with his family, and his son, sculptor Jonathan Shahn, was an extremely gracious tour host, and was particularly descriptive about life in the house and its development, including the George Nakashima additions (1960 and 1965). We also toured the Mallach House, and visited the Roosevelt School. The Roosevelt School design was based on preliminary sketches by Kahn, and included a large mural by Ben Shahn in the lobby. The Jersey Homesteads were renamed Roosevelt, New Jersey in 1942 in honor of Franklin D. Roosevelt after his death.

One of Kahn’s next major residential commissions was the Oser House (1940-42). Kahn designed the Oser House in the Philadelphia suburban community of Elkins Park. Here we saw the beginning of Kahn’s architectural vocabulary for his residential projects. Most of these projects were made of intersecting and/or joined cubes, and the massing of this project was particularly simple, with the two main volumes being co-joined cubes, one of local masonry and the other of wood. The wooden section was later expanded.

We also viewed the Wharton Esherick House and workshop in Malvern, Pennsylvania. Wharton Esherick was a painter turned sculptor who worked mainly out of his home studio. Kahn designed Esherick’s workshop (1955-57) in a manner very much unlike any of his other major commissions. While certain aspects of design motif remain – heavy massing, geometricality – the rest is an experimentation in color and bold, sharp angles, actually echoing the eccentric Wharton Esherick House itself. The studio is turned away from the driveway, but the rear elevation is what reveals the Kahn hand more dominantly- a façade full of windows that flood the interior with natural light.

Kahn designed another house for a member of the Esherick family, the Margaret Esherick House (1959-61) in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania (not far from George Howe’s High Hollow country house). Margaret Esherick, the niece of Wharton Esherick, commissioned the house as a residence for a single woman without a family, therefore the program of the building was different from many of Kahn’s other residential ventures. The building was divided into two main spaces, clearly articulated in the façade, with a two story living room which was programmatically divided from the kitchen and private living spaces by the centrally located stairs. Several of the best features of the Esherick house included the breezeways afforded by large windows, the kitchen designed by Wharton Esherick, and the “T” motif that was seen in everything from the smallest details to the fenestration pattern on the façade.

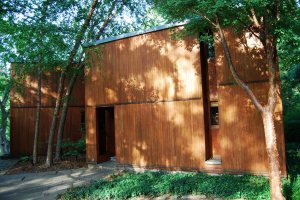

The Fisher House is a demonstration of Kahn’s maturation with the use of wood and stone in his residential work. The group toured the exterior of the house, and was highly impressed with the simple volumes and intense detailing in the wood work. The use of wood, however, became problematic for the residents when woodpeckers began to destroy the exterior.

The Korman House was the last house Kahn designed, and fittingly the last house the tour group visited. The Kormans were exceedingly welcoming, and gave a tour of the house, citing influences, inspirations, and the vision that they shared with Kahn for the creation of the house. Kahn designed a house program that fit the characteristics of the family- Kahn was interested in creating a home that embodied the values and priorities of a young family with three active sons. Continued themes at the Korman House included a tight integration and contrast of materials- wood and brick in this case, the “T” shape motif in the fenestration, an efficiency of space, as well as an abundance of light on the interior of the house.